What Would Have Happened Anyway?

Let’s suppose we’ve ruled out luck as an explanation for our data. Suppose we have inferred that something in the assaults data really did change around the time the new closing-time policy came into effect. Attributing this change to the new closing times is another matter entirely.

It would be easy to determine the true effects of the new policy if we knew how many assaults we would have seen had the policy never gone into effect. To say that A caused B is to say that B would not have happened without A. But we only have data with the policy change. Every statement about cause is really a statement about the way the world would have been without that cause, a counterfactual statement. This is one reason why causation is so tricky: it requires reasoning about imaginary worlds that we can never observe directly.

This problem can only really be solved with a time machine. We can go back in time, prevent the new closing time from taking effect, then wait to collect equivalent data in this divergent universe. Lacking a time machine, we’ll once again use a model, a way of describing the alternate histories we can’t ever observe directly.

If we had two identical copies of New South Wales, we could just change the policy in one city and not the other, and compare the results. This is the logic behind the controlled experiment where you give a new drug to the treatment group and not to the control group. Journalists don’t normally get to design experiments, and anyway there are never two identical cities to experiment on. But we could make comparisons with similar cities or neighborhoods.

Just this sort of comparison casts great doubt on an attempt to reduce gun violence in Richmond, Virginia, in the late 1990s. Project Exile aimed to reduce the number of murders by increasing the punishment for illegal gun possession (such as when a previously convicted felon is found to be carrying a gun). The minimum sentence was effectively increased from five to 10 years by shifting all such cases from state to federal courts.

At first glance, it worked.

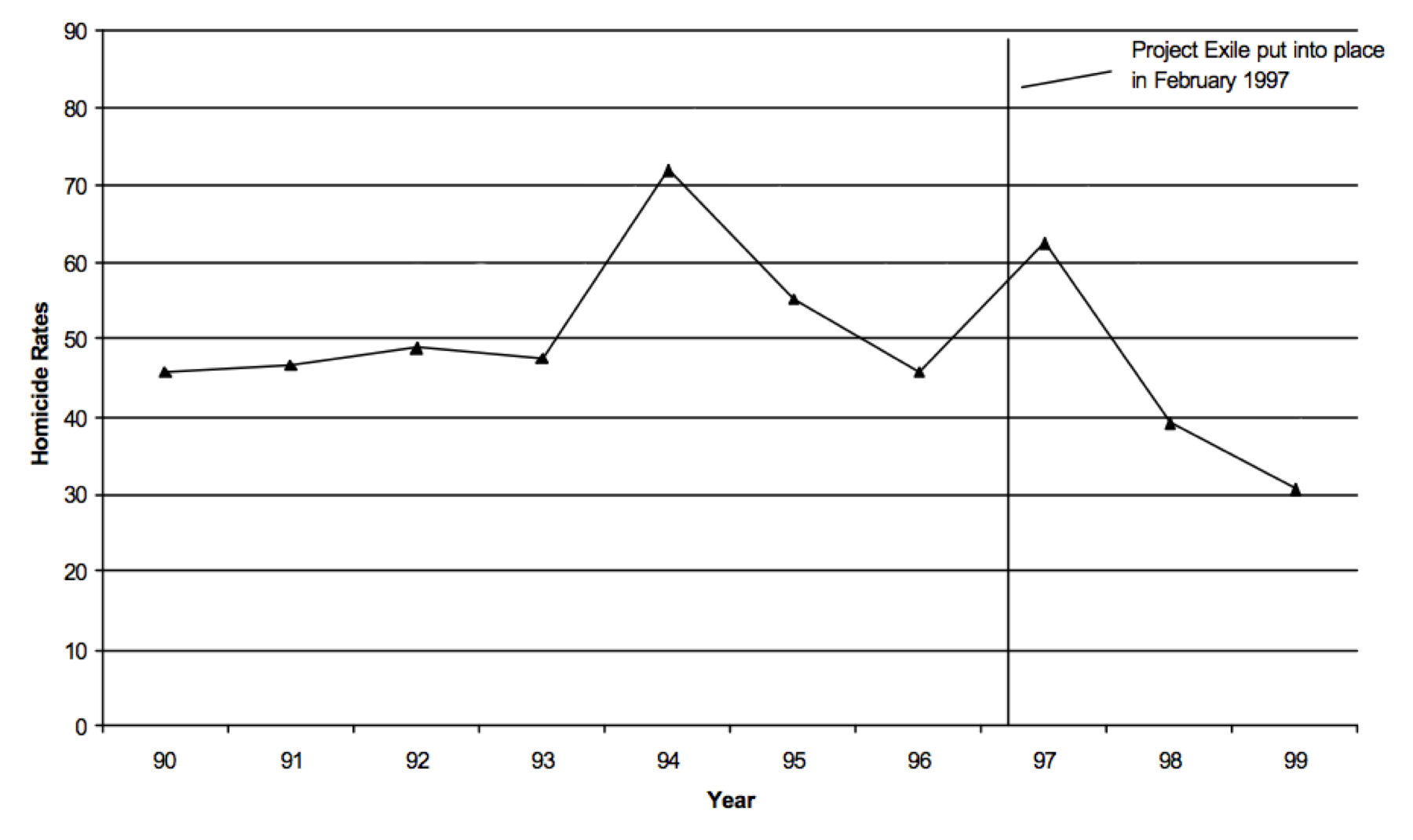

Gun homicides per 100,000 residents in Richmond, Virginia, before and after Project Exile. Adapted from Raphael and Ludwig, 2003.35

Gun-related homicides—by far the majority of homicides—decreased after Project Exile went into effect. The policy was widely lauded as a success by the National Rifle Association, The New York Times, and President George W. Bush.

But the evidence for harsher sentences in Richmond is not nearly as strong as it is for earlier closing times in New South Wales. First, the data is very scarce. There are only three data points after the program was established, for 1997, 1998, and 1999. Further, the number of gun homicides actually increased dramatically for 1997, even though gun possession offenders were tried in federal courts beginning in February 1997. However, 1998 and 1999 do show solid declines, ending lower than anything in the previous decade.

Let’s table for a moment the question of chance; with only three data points, luck becomes a real concern. Suppose we believe the decline is real and permanent, and not just fluke due to natural variation. We still have the problem of attributing cause to Project Exile and not something else. Really what we need is another identical Richmond to show us the alternate history where Project Exile never happened.

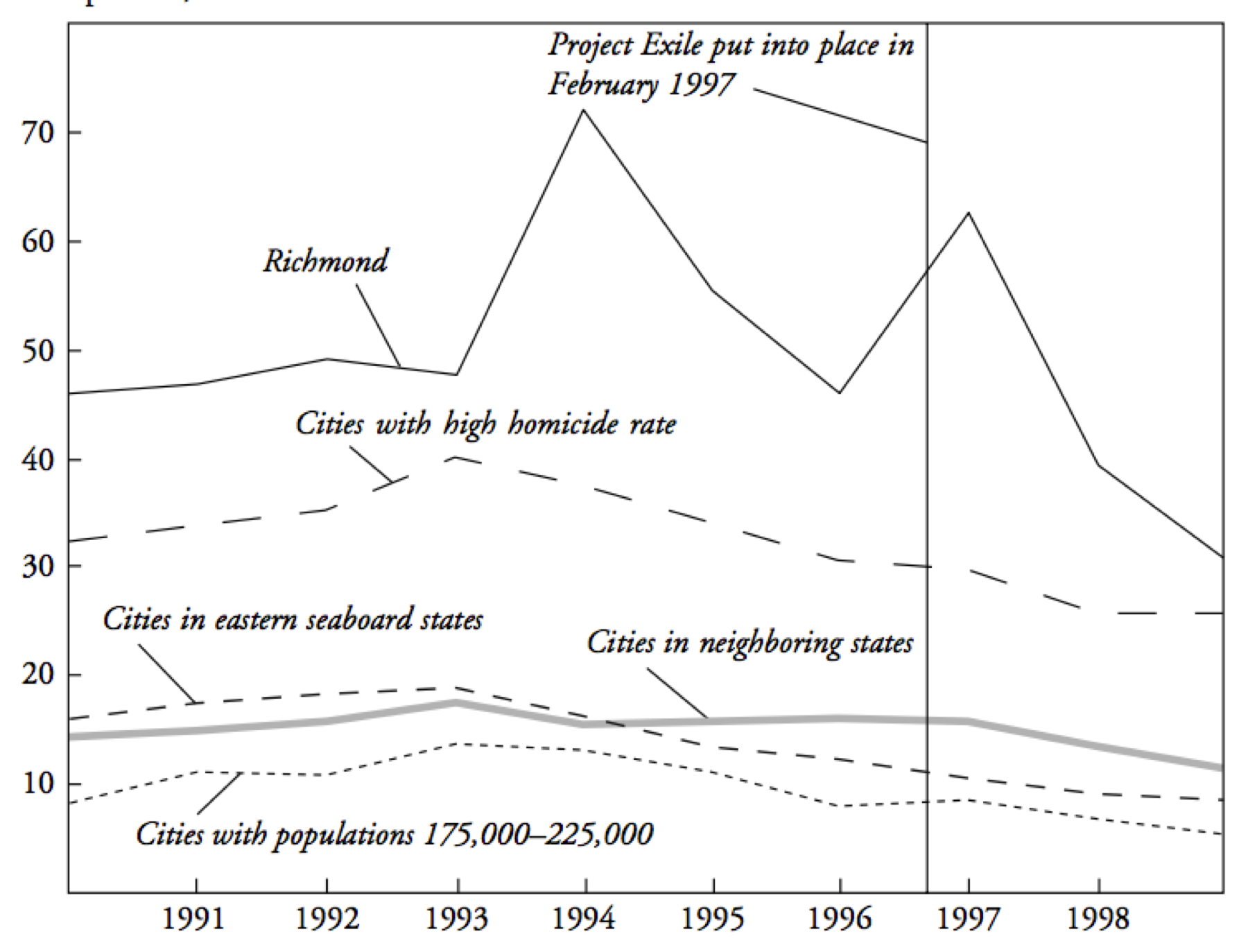

We don’t have another Richmond, but there are many other cities. If those cities are similar enough in the right ways, they might approximate the lost history where Richmond never had a Project Exile. Here’s the homicide rate data from other cities which are similar in various ways, but none of which implemented such a program.

Gun homicides per 100,000 residents in Richmond, Virginia, before and after Project Exile, compared to other cities. From Raphael and Ludwig, 2003.36

Virtually every city in the United States experienced a decline in gun violence in the late 1990s. In fact violent crime of all types decreased all through the country during the 1990s. No one really knows why, though there are many theories.37 Evidently, you didn’t need to change sentencing guidelines for illegal gun possession to see a drop in gun crime in the late 1990s.

Maybe you can still say that Richmond had a larger decline. But Richmond also had more crime to begin with, and a big spike in 1997. Proportionally, as a percentage change, Richmond’s decrease was well in line with other cities. You can see this if you plot the data on a logarithmic scale.

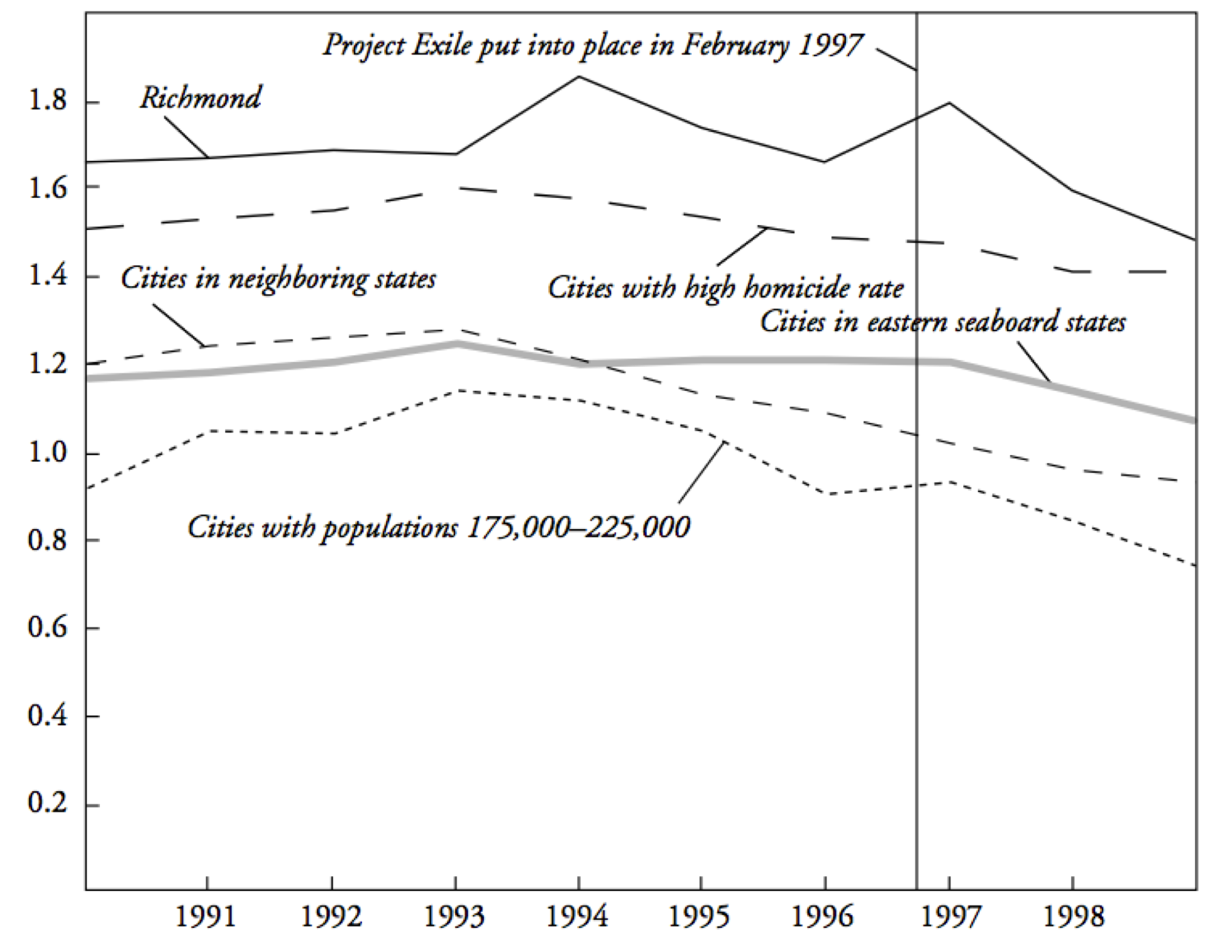

Gun homicides per 100,000 residents in Richmond, Virginia, and other cities, on a logarithmic scale. From Raphael and Ludwig, 2003.38

Each vertical step on a logarithmic scale corresponds to an increase by a constant multiplier, which means we are comparing percentage change instead of absolute numbers. When we compare this way, Richmond doesn’t look particularly better than other types of cities. Most cities experienced a drop in gun violence of about the same percentage as Richmond, which appears on this chart as a decrease of about the same slope. This is evidence that doing nothing would have been just as effective.

Here you can have an argument about whether percentage change or absolute numbers are the right way to compare a drop in crime between cities. You can also try to construct more elaborate analyses showing that while murders in Richmond would have dropped anyway, Project Exile made them drop more. We’re far from the last word, but we’re also past a simple argument that Project Exile caused the observed fall.

And, of course, you can jump out of this framing entirely and ask if increased punishment is really the way that we, as a society, want to deal with a type of crime that primarily involves and affects already disadvantaged groups. As always, the data is never the full story.

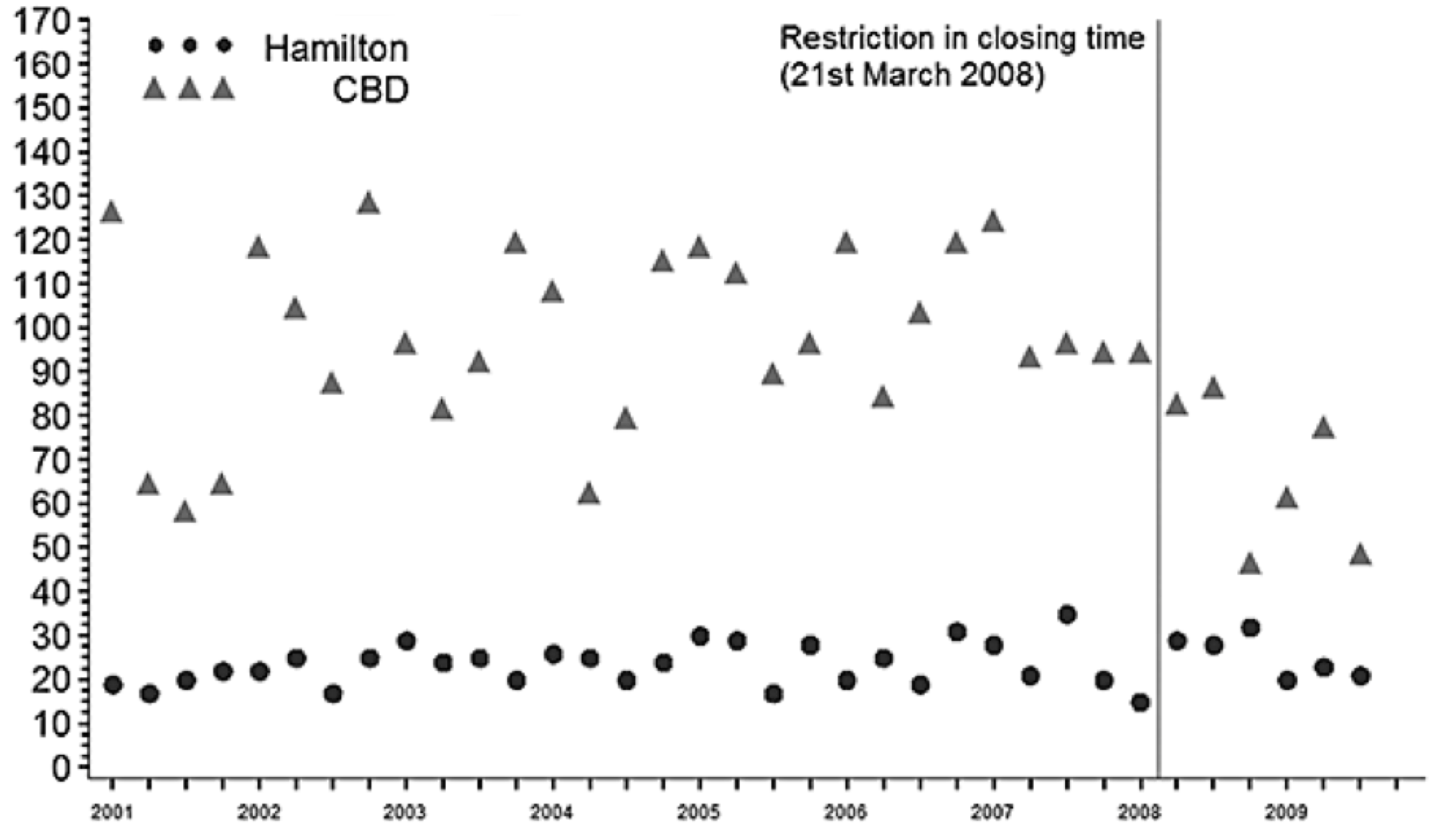

Back to New South Wales, does the closing-time policy change suffer from the same sort of “would have happened anyway” problem? Again, the theoretically perfect test would require an identical copy of the city. But we do have data from the adjacent neighborhood of Hamilton, which did not see a restriction on closing times.

Number of assaults per quarter in the central business district (CBD) of New South Wales, where closing time was restricted to 3 a.m, and the neighboring region of Hamilton where it was not. From Kypri, Jones, McElduff and Barker, 2010.39

And sure enough, there was no apparent reduction in assaults in Hamilton. The main weakness of this sort of comparison is that Hamilton is not perfectly matched with the area where the closing time was changed. It has fewer bars and a far lower rate of assaults to begin with. Still, this comparative data provides a minimal sanity check. We need to exclude the possibility that something else happened around the same time that lowered assault rates generally. That’s what seems to have happened with homicides in American cities in the late 1990s. The other reason for looking at the data for the adjacent district is to make sure that crime was actually reduced, not just displaced to nearby areas.

Any claim of cause is implicitly a claim about data from a world we don’t ever get to see: a world where the cause never happened. it’s worth thinking about how to approximate this world through comparisons or modeling. Just looking for increases or decreases is not enough. As the Project Exile researchers put it:

One larger lesson from our analysis of Richmond’s Project Exile is the apparent tendency of the public to judge any criminal justice intervention implemented during a period of increasing crime as a failure, while judging those efforts launched during the peak or downside of a crime cycle as a success.40

And that’s just not right. The correct comparison is not “up or down,” but “what would have happened otherwise?” This applies just as well to the question of whether chicken soup cures colds as it does to the question of whether harsher sentences deter crime.