Analysis

It may well be that several explanations remain, in which case one tries test after test until one or other of them has a convincing amount of support. - Sherlock Holmes21

It’s been said that data speaks for itself. This is nonsense.

It’s true that going and looking usually beats sitting and thinking. That’s the core idea of empiricism and the point of collecting data. And it’s true that data can be revealing and insightful. Sometimes you look at a graph and say “aha!” and feel you understand the world a little better. In that moment there is the sensation that the data is speaking, that it tells a clear story.

But the data didn’t tell a story, you did. You saw a story that connects the data to the world. Are you right? Ideally, your story is thoughtfully corroborated by many sources. But if you’re going to use data as evidence, you have to understand what it does and doesn’t say.

This chapter is about how to draw true meanings from true data. There are mathematical rules which say that two plus two never equals five. There are formulas that encapsulate the logic of working with chance and cause. There are basic principles of investigation, such as testing your guesses. And there are fundamental limitations to knowledge, the cases where we must admit we can’t know the answer, at least not with the data we have.

This doesn’t mean there’s a single right answer in every case. All data analysis is really data interpretation, and relies on combining data with something else, such as previously known facts or cultural knowledge. Data, on its own, has no meaning at all. Imagine a spreadsheet with no column names. It would just be numbers, indecipherable and useless.

The necessary context enters in many different ways. Data can’t be understood without knowledge of the quantification process that created it. Statistical work usually requires assumptions tied to common knowledge: total kale consumption can’t be more than a small fraction of total food consumption, and lower cancer rates are better. But the culture and the journalist are also part of the context that creates meaning. Every society has particular worries that shape what is newsworthy, while individual journalists have specific beats and interests. Actually the context comes before the data; it tells us what data is relevant, even what questions are relevant.

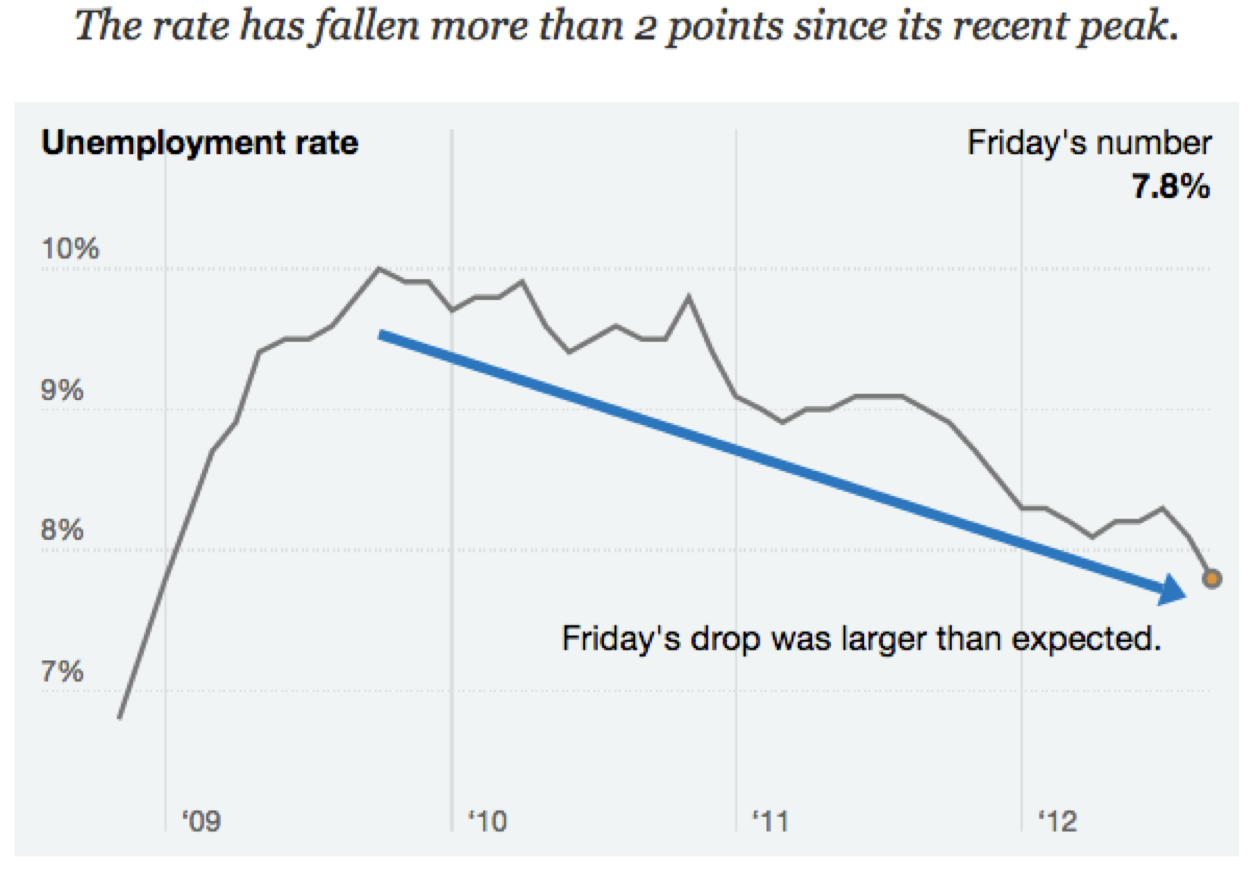

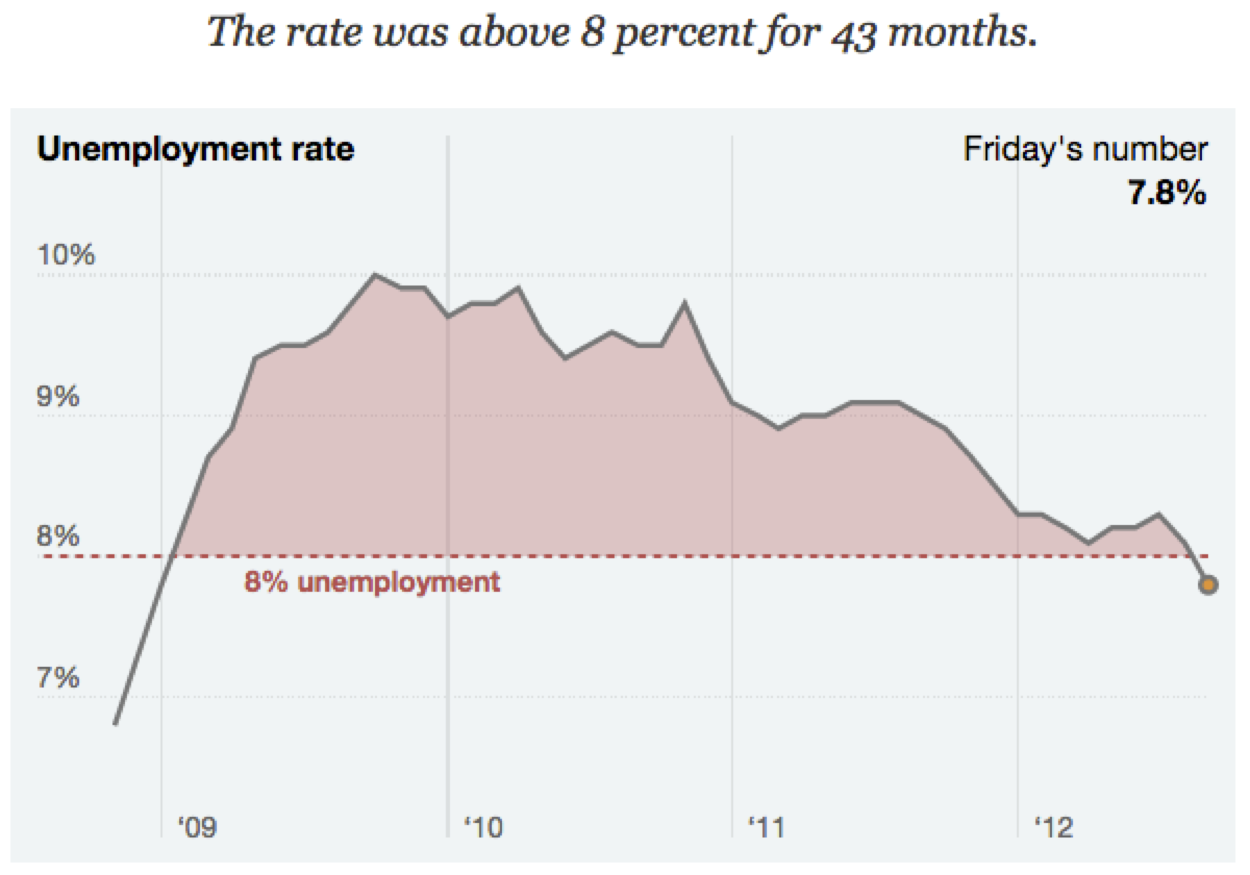

Context is where subjectivity enters into data interpretation. The New York Times illustrated this with two different interpretations of the same unemployment data, describing how a Democrat and a Republican might see things.

How Democrats and Republicans might interpret the same unemployment data in different ways.22

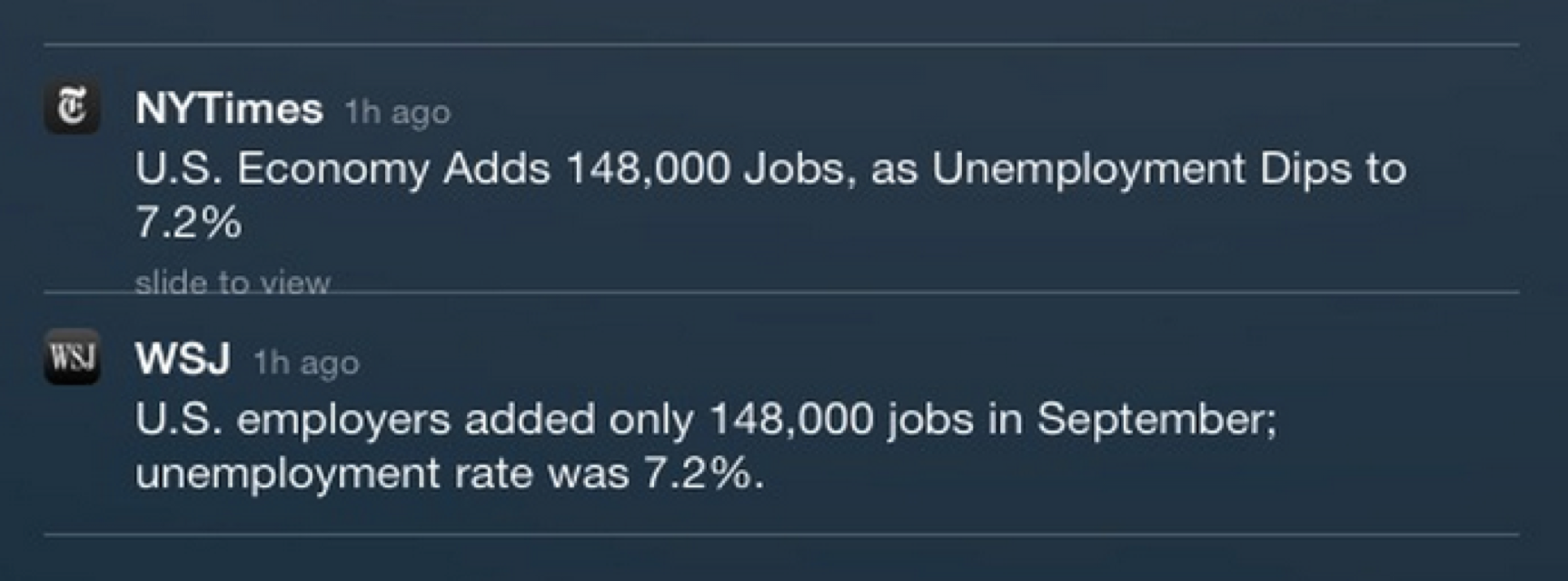

But it’s not just politicians who have different perspectives. Journalists can and do disagree on the interpretation of a single number.

Headlines on October 22, 2013.23

Both headlines are perfectly true. The difference between them is down to whether 148,000 merits “only”—is it a big or a small number? This could also be a matter of expectations: perhaps The Wall Street Journal was hoping to see a larger increase in jobs.

This subjectivity may seem disheartening. In the sciences “subjective” is sometimes used as an insult. Subjective things are personal, dependent on who is speaking, maybe a matter of taste. Wasn’t data supposed to be objective? Wasn’t it supposed to avoid the arbitrariness of opinion and bring us closer to the truth?

Data interpretation may not be mathematical logic, but nether is it nihilist. Our interpretations must be faithful to reality. Out there in the world a policy changed crime rates, or it didn’t. The wage gap is some specific level and no other. Careful measurements show climate change is driven by human activity through particular mechanisms, or they don’t. All of these are quantitative statements that involve quantification choices—sometimes controversial choices. But once you pick a counting method, reality will see that you end up with a particular number, which is of course the point of counting. Just like a scientist, a journalist can’t make up data, ignore evidence, or condone logical fallacies. it’s equally important to know when you don’t know, when you can’t answer the question from available data.

Yet the constraints of truth leave a very wide space for interpretation. There are many stories you could write from the same set of facts, or you could decide that entirely different facts are relevant. Subjectivity is at the core of journalism, because there is no objective theory that tells us which true stories are the best. But “subjective” doesn’t necessarily mean “personal.” Culture is widely shared and people live in networks, and journalism requires a broad dose of societal knowledge. Journalists especially need to understand the common knowledge and values of the audience—even if just to challenge them. That audience is never uniform, and different people will have different concerns, experiences, and perspectives. Every time you ask yourself “what is the story here?” you are bringing the audience into your work.

Finding a story in the data will always be an act of cultural creation. But those stories must still be true! So the rest of this chapter is an introduction to three big ideas that can help draw truth from data. The first is the effect of chance, randomness, or noise, which can obscure the real relation between variables or create the appearance of a connection where none exists. The second is the nature of cause, and the situations where we can and can’t ascribe cause from the data. Above all is the idea of considering multiple explanations for the same data, rather than just accepting the first explanation that makes sense.

My goal is to give you the higher-level logic of the whole process of statistical analysis. For any particular problem you will need specific technical tools, but those choices must be guided by a larger framework.