The Globe and Mail

In March of 2015, Toronto’s Globe and Mail installed the first SecureDrop in Canada. In an article announcing the launch, The Globe’s editor-in-chief David Walmsley wrote, “SecureDrop is the 21st-century equivalent of the manila envelope: It provides you with an anonymous venue for relaying material you believe to be in the public interest and you have no other way to get it out publicly.”13

Deputy production editor Alasdair McKie, who is one of the primary caretakers and facilitators of The Globe’s SecureDrop, said that the system quickly proved itself useful, yielding a story almost immediately after its launch. The use of the system is largely tied to The Globe’s investigative team. A handful of these reporters have been trained to use SecureDrop and check it roughly three times a week for promising material.

McKie’s account of messages received in its SecureDrop also suggests that The Globe might be less afflicted by spam and trolls than other news organizations. “The majority of the submissions that we’ve received, I would call good faith submissions from potential sources,” McKie said. He continued:

They’re not intentionally wasting our time. They’re not intentionally sending us something that’s not of journalistic value. They’re not sending us garbage on purpose just to yank our chain. That is not super common. It does happen. But it’s not something that’s been a problem for us.

Like most other informants in this study, McKie declined to point to specific cases in which tips and documents from SecureDrop led to published stories. Furthermore, he said that The Globe established an explicit policy before launching SecureDrop that their organization would never, under any circumstances, indicate that a source had come through this particular channel.

Beyond its use as a reporting tool, McKie also highlighted that running SecureDrop reflects an awareness of our society’s present surveillance dilemma and a respect for the press’s role in highlighting this reality:

The fact that there are people who are willing to contact us over SecureDrop, who are not willing to contact us through another avenue, underscores for people not just the editorial leadership in the newsroom, but also just the company in general, that information security is a fact of life now. And some of the other initiatives, like getting people signed up with PGP keys and that sort of thing, is something that is going to be part of our lives. And the sooner we incorporate that into the way we go about our business, the better it is for news organizations, in particular, because we are the focus of policy-making information in our society.

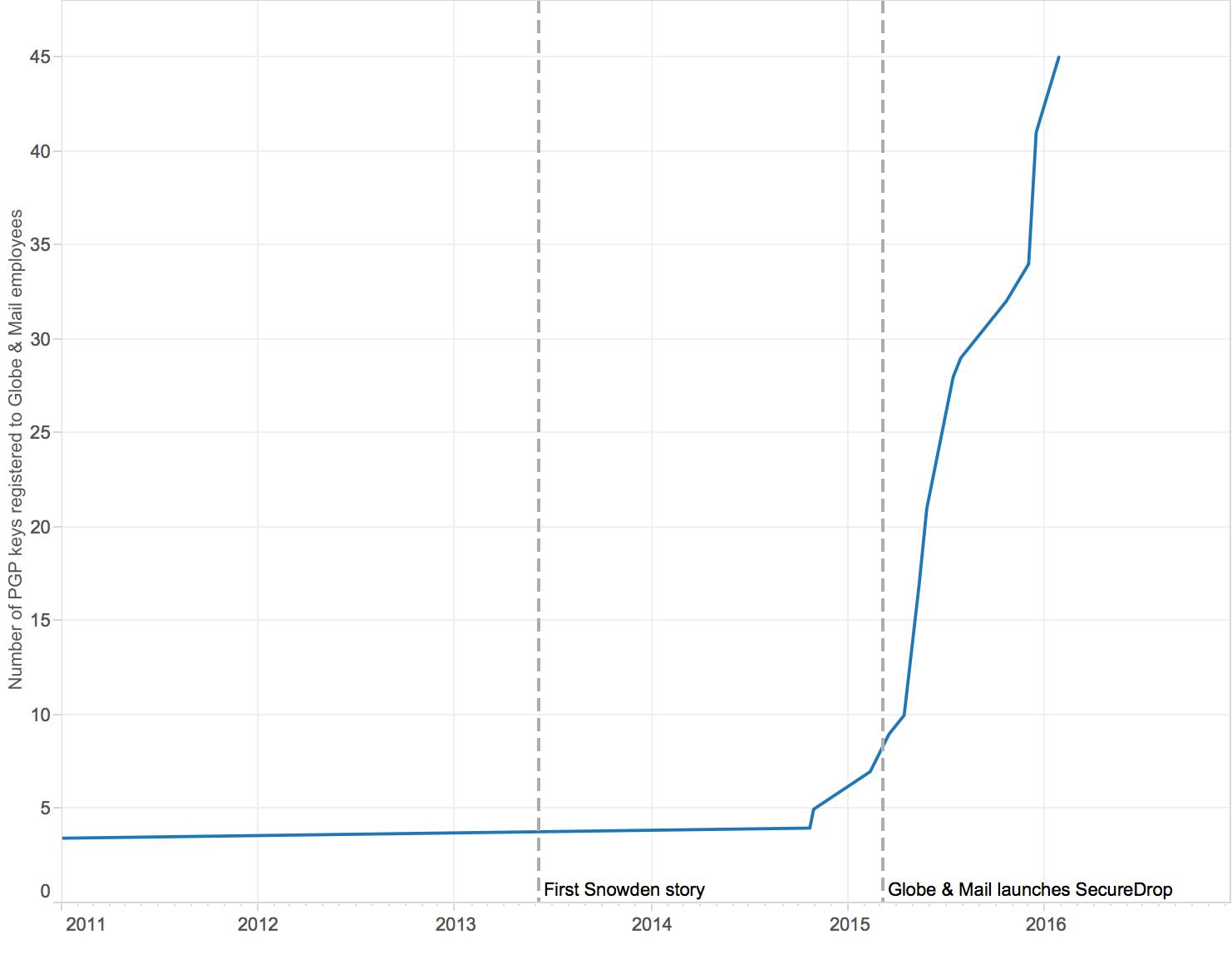

According to records at the MIT key server, only a few Globe and Mail staff members were registered with PGP before their organization’s SecureDrop was installed. McKie said that many of the advances in security training in their newsroom took place in preparation for the installation of SecureDrop. Records also indicate that the majority of Globe PGP keys were registered in the months following the launch of its SecureDrop. During the 2015 calendar year, twenty-eight more of the paper’s journalists registered PGP keys, placing The Globe in the top third of organizations studied here in terms of total registrations. It ranks just ahead of The Wall Street Journal and just below the The Guardian.

Number of public key registrations over time at The Globe and Mail.

Number of public key registrations over time at The Globe and Mail.