How Automated Journalism Works

Current solutions range from simple code that extracts numbers from a database, which are then used to fill in the blanks in pre-written template stories, to more sophisticated approaches that analyze data to gain additional insight and create more compelling narratives. The latter rely on big data analytics and natural language generation technology, and emerged from the data-heavy domain of sports reporting. Both major providers of natural language generation technology in the United States, Automated Insights and Narrative Science, began by developing algorithms to automatically write recaps of sporting events. For example, Narrative Science’s first prototype, StatsMonkey, which emerged from an academic project at Northwestern University, automatically wrote recaps of baseball games.9 Baseball served as an ideal starting point due to the wealth of available data, statistics, and predictive models that are able to, for example, continuously recalculate a team’s chance of winning as a game progresses.

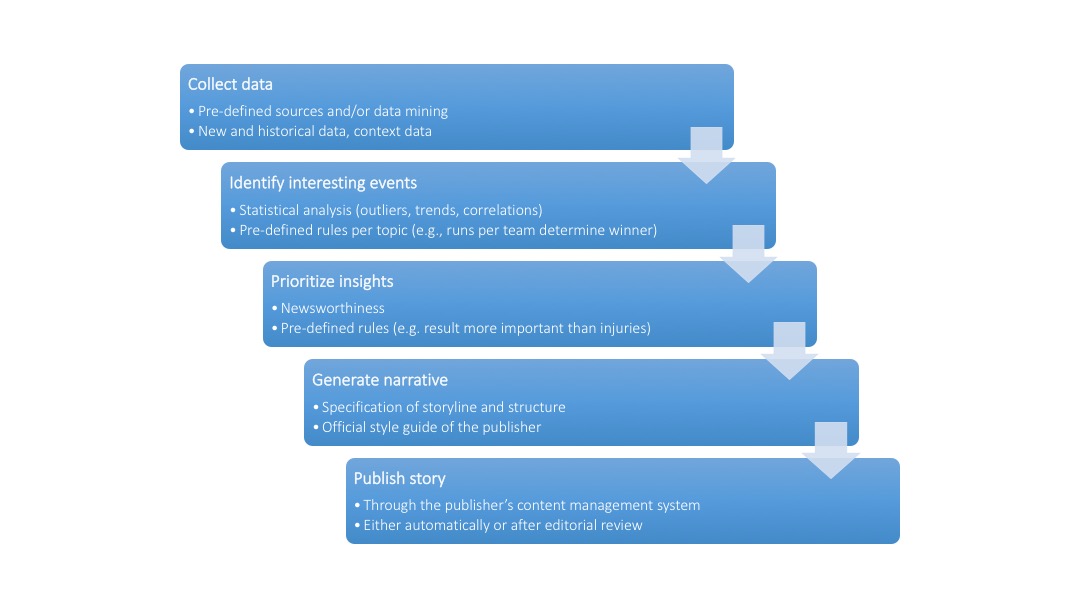

Figure 1 shows the basic functionality of state-of-the-art natural language generation platforms.10 First, the software collects available data, such as—in the case of baseball—box scores, minute-by-minute plays, batting averages, historical records, or player demographics. Second, algorithms employ statistical methods to identify important and interesting events in the data. Those may include unusual events, a player’s extraordinary performance, or the decisive moment for the outcome of a game. Third, the software classifies and prioritizes the identified insights by importance and, fourth, arranges the newsworthy elements by following predefined rules to generate a narrative. Finally, the story can be uploaded to the publisher’s content management system, which could publish it automatically.

Figure 1: How algorithms generate news

During this process, the software relies on a set of predefined rules that are specific to the problem at hand and which are usually derived from collaboration between engineers, journalists, and computer linguists. For example, within the domain of baseball, the software has to know that the team with the most runs—but not necessarily the most hits—wins the game. Furthermore, domain experts are necessary to define criteria of newsworthiness, according to which the algorithm looks for interesting events and ranks them by importance. Finally, computer linguists use sample texts to identify the underlying, semantic logic and translate them into a rule-based system that is capable of constructing sentences. If no such sample texts are available, trained journalists pre-write text modules and sample stories with the appropriate frames and language and adjust them to the official style guide of the publishing outlet.