Sharing Personal Experiences

Several news organizations have developed a suite of stories by issuing both structured and unstructured call-outs to targeted communities. While they might maintain a general outline of the stories they want to do, they seek contributions that may change the narrative, reveal surprising trends, uncover unknown sub-groups, or point to discrete stories for coverage.

Honolulu’s Civil Beat, for instance, crowdsourced part of its “Living Hawaii” series, publishing first-person narratives from residents. “Nothing is more common in Hawaii than struggling with the cost of living,” said deputy editor Eric Pape. “It’s so damn expensive here. This allows people to say, ‘Here’s my story about this.’” Civil Beat also invited first-person narratives and opinion about the conflict over Mauna Kea, a dormant volcano where scientists are looking to build a telescope on what many residents consider sacred land. Pape said the topic reflects the differences of opinion in Hawaii about a number of issues: how people think about native Hawaiians, money, nature, science, etc. “It’s a sweet spot for us,” Pape said. “We are here to highlight problems and obstacles to solutions, as well as possible solutions.” Sometimes these crowdsourcing efforts begin such robust conversations that news organizations take an additional step and create venues such as Facebook pages for continued discussions after the stories are produced.

During Elizabeth Rosenthal’s work on health care costs, The New York Times eventually permitted a Facebook Group page that now has more than 6,500 members. Rosenthal acknowledges that it’s an open page where any journalist can lurk and mine story ideas just as she does. “I think my editors feel that’s fine. But that was a discussion,” she said. Similarly, Pro Publica’s Patient Safety Facebook Group of more than 3,300 members33 reporting grew out of reporting by Marshall Allen, Sisi Wei, and Olga Pierce that found one million people each year suffer harm when treated in the U.S. health care system.34 They explored everything from dangerous dialysis centers, to unsafe hospitals, to surgical complications in operating rooms.

Overall, ProPublica has been a leader in eliciting personal contributions that help structure new narratives.

Case Study—ProPublica

No other U.S. news organization has cultivated the art of crowdsourcing

like ProPublica. With patience and acumen, the eight-year-old nonprofit

startup has both embraced a unique mindset and developed a robust

toolkit to transform enterprise journalism.

No other U.S. news organization has cultivated the art of crowdsourcing

like ProPublica. With patience and acumen, the eight-year-old nonprofit

startup has both embraced a unique mindset and developed a robust

toolkit to transform enterprise journalism.

The mission, simply put, is to “find people in the know,” said Amanda Zamora, senior engagement editor who has spearheaded ProPublica’s crowdsourcing efforts in recent years. That is accomplished by building “getting involved” on-ramps, and soliciting sources and contributions through formal call-outs. It also entails cultivating source communities with high-touch communication and dynamic givebacks.

“It’s sort of like we’re building a tree. We plant one and it’s very skinny, but we soon get a sense of whether it’s about to grow,” she said. ProPublica’s mindset is all about transparency and collaboration. “One thing ProPublica is not afraid to do is to investigate in the open,” said Charles Ornstein, who credits crowdsourced contributions for advancing many of his health care stories, including Dollars for Docs and experiences with the Affordable Care Act. “You sort of announce what you are working on. It’s sort of scary letting other people know. But you are also staking your turf.” Last year, ProPublica moved away from Google Forms because it needed to better organize the vast amounts of data it was gathering. As of mid-September 2015, Zamora counted at least 37 call-outs since 2009 that generated 10,953 responses just from surveys. Another 13,400 people have signed up to participate in other ways.

ProPublica found a solution in Screendoor, a database tool built to handle government requests for proposals. “We’ve taken their RFP platform and turned it into a story platform,” Zamora said.

Over the years, crowdsourcing has contributed to an array of ProPublica news exclusives focusing on patient safety, nursing home inspections, its Surgeon Scorecard, and more. Input comes via call-outs and questionnaires and also through its “Reporting Network” of volunteers who engage in reporting tasks such as reviewing political ad spending in its Free the Files project.35

ProPublica deploys both structured and unstructured solicitations to collect personal stories and documents, identify sub-groups with stories to tell, and build communities of stakeholders.

Here’s how one recent structured call-out worked. In late June 2015, Charles Ornstein and The Virginian-Pilot’s Mike Hixenbaugh wanted to explore the effects of Agent Orange on Vietnam veterans and their children. They also wanted insights on stories they didn’t know about.

So, ProPublica invited service members and their families to share their experiences. Ornstein wrote an advance story, then ProPublica went to work issuing call-outs for information on its website, in social media channels, and in a podcast. It also mined veterans’ communities—even the websites of naval ships dispatched to the war zone.

In the first 12 weeks, more than 2,900 people responded. “This is an extraordinary response,” Ornstein said. “People want to share their stories. They’ve been waiting for this opportunity.”

Screendoor captured their stories in its highly searchable database. Terry Parris Jr., ProPublica’s community editor, began to solicit documents to verify dates of service, wrangle photos, and record audio stories. “I’m on the frontlines of the community coming in,” he said. By mid-September, the crowdsourcing helped generate an early story on a subset of stakeholders: the Blue Water Vets, who were being denied benefits because they sailed not in the brown waters of Vietnam’s inland waterways but in the blue waters of the seas off Vietnam, where they likely drank Agent Orange-polluted water.

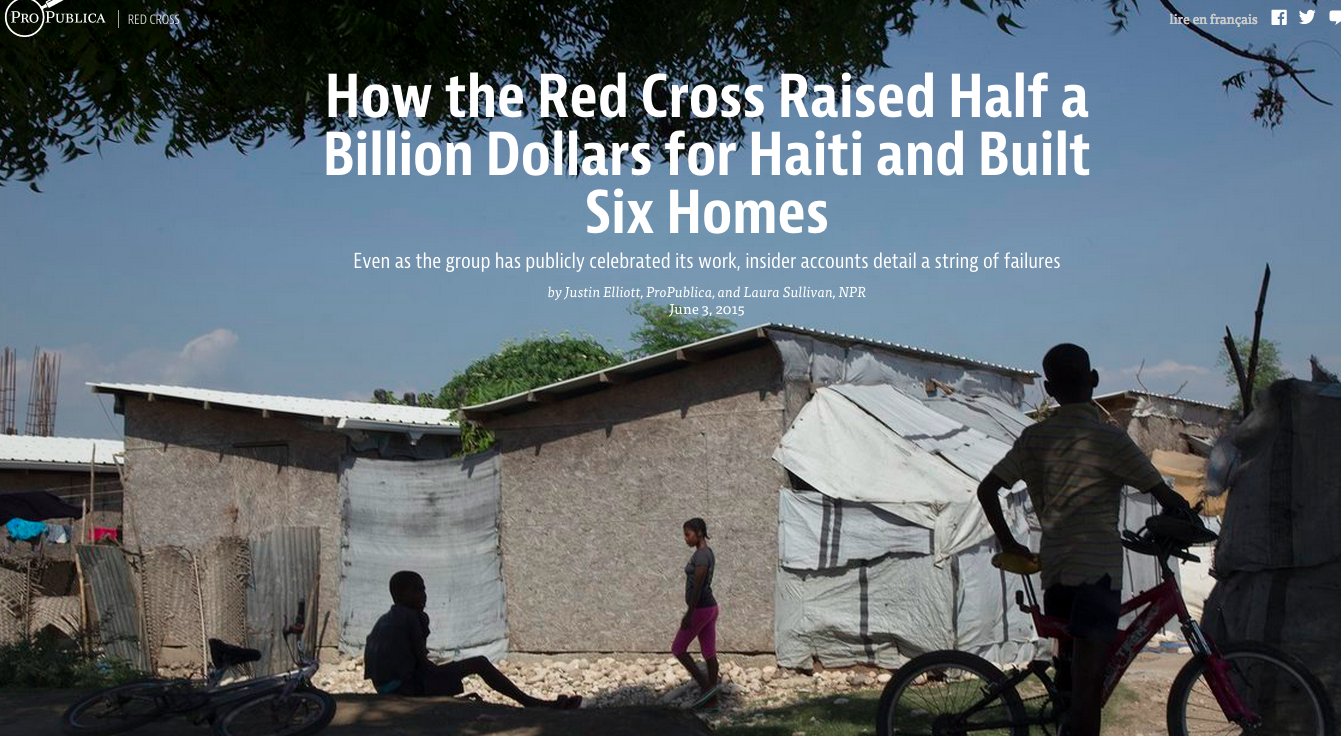

Not all of ProPublica’s crowdsourcing efforts involve requests to complete questionnaires. In fact, significant stories by Justin Elliott, Jesse Eisenberg, and NPR’s Laura Sullivan on Red Cross relief spending during the 2012 Superstorm Sandy and the 2010 Haiti earthquake initially engaged in an unstructured call-out. Essentially, the journalists urged readers to email Justin “if you have experiences with or information about the Red Cross, including its operation after Sandy.”

Only a few emails arrived at first, until ProPublica reported that the Red Cross was fighting its FOIA request to the N.Y. Attorney General because the information might potentially disclose “trade secrets.” More sources weighed in, leaked documents arrived, and people urged the reporters to look into Haiti relief spending as well.

“There’s no way we would have gotten the tips we got without that [email us] line,” Elliot said. “People need a nudge. Just because of Sandy, I’ve been adding these lines to everything I’ve written.”

The ProPublica/NPR reports raised questions about how the Red Cross spent millions in donations raised for victims. One impact: recently proposed federal legislation requiring the charity, which has a government-mandated disaster-response role, to open its operations to outside oversight.

“Universally, these are people who worked for or volunteered for the Red Cross for a long time,” Elliott said. “They cared a lot about the organization and thought there were unethical decisions . . . might be some management incompetence or mismanagement of money.”

Said Zamora, “Every reporter who has worked on a call-out will tell you they found sources or insights that substantively impacted their stories.”

One outcome of ProPublica’s crowdsourcing is “we have way more stories and sources than we can use,” said Zamora, who wants to “catalyze other reporting” by making that data available to journalists who want to find their own stories in it.

Screendoor will play a role in managing that network of reporters because it can identify contributors by location. The database, said co-founder Clay Johnson, sends an immediate acknowledgement to a contributor. It allows ProPublica to filter and rate responses, add comments into the responses, send a note to a specific sub-group of people, track the emails sent, and share all project updates with participants in a personalized way.

“I can say, ‘Dear Barry,”’ Ornstein said. “You told us you have cancer, diabetes, or [suffered from] a heart attack.”

Zamora also plans to use it to “dynamically expose pieces of the story” through vignettes, pull quotes, or audio clips from contributors so ProPublica can continue giving back to the community and tease out more input while the crowdsourcing process is ongoing. Next up: ProPublica is partnering with Yelp in a project to align Yelp’s “qualitative reviews with ProPublica’s objective data” on medical services, Ornstein said. He added that the partnership will give ProPublica access to Yelp’s “firehose” of more than a million reviews. The Knight Foundation recently awarded ProPublica a $2.2-million grant to help advance its audience engagement work and train others in its techniques. “I feel we are just on the cusp of finally being able to realize what I’ve wanted to do,” Zamora said.