Engaging Audiences

Not all crowdsourcing is intended to produce investigative series, build sophisticated databases, or tease out powerful narratives from people with knowledge of something reporters want to pursue.

Many news organizations are making it a priority to connect with their audiences in ways that are as much fun and engaging as they are informative. Others connect with real-time, useful information.

“Whenever we have active weather, crowdsourcing is at the heart of what we do,” said Jason Samenow, The Washington Post’s weather editor. He is also chief meteorologist for the Post’s Capital Weather Gang, marshaling contributions from its 180,000 Twitter followers and 66,600 Facebook fans. During snowfalls, “people send us pictures of their rulers in the ground,” he said. Likewise, the for-profit NYC’s CleverCommute.com is now transitioning hundreds of thousands of email contributors to a new app that will collect their alerts on real-time commuter train hiccups and relay them to New York’s huge commuter train community and local media clients. Public broadcaster WNYC is one of the standouts in crowdsourcing its listeners about everything from the useful (e.g., has the city snow-plowed your street yet?) to the whimsical (e.g., what is your sleep pattern?). “We need to be good at this because it’s the source of very valuable content,” said Jim Schachter, WNYC’s vice president for news. Public radio, with its well-received call-in shows, is uniquely situated to develop call-outs that command a lot of contributions, as well as donors. “In Bored and Brilliant, we asked you to build a replica of your dream house out of the contents of your wallet and then take a picture of it and share it with us,” Schachter said. “If you’re willing to do all that work, it’s a fairly small ask of us to say, ‘Will you be a member?”’

Case Study—WNYC Public Radio

WNYC public radio in New York specializes in crowdsourcing with intense community engagement. Recent projects have tasked listeners with tracking soil temperatures to predict when cicadas would emerge from the ground, to assessing their sleep patterns and encouraging them to turn off their mobile phones and test their creativity in its Bored and Brilliant challenge.

What’s the secret? “It has to do with purposefulness and a reasonably active effort to learn from what we’ve done in the past,” said Jim Schachter, WNYC’s vice president for news. “When we launched into the sleep project, we were thinking what worked and didn’t work in the cicada project. And when we launched Bored and Brilliant, we were thinking what worked and didn’t work in sleep and cicada.”

Part of the station’s secret sauce? Its popular Brian Lehrer morning call-in show.

“We have a call-in show and host that for 25 years have been honing how to pose questions to people so the board will light up and Brian won’t be there talking to himself,” Schachter said. “I don’t want everybody else to start a talk show because our secret weapon would be stolen. But if every newsroom acted like it had one, what would it be like for that newsroom?”

Integral to many projects is John Keefe, senior editor for data news. A journalist with technical skills, Keefe was central to the Cicada Tracker project, which provided directions on how to build a soil-temperature measuring device.44 Ultimately, 1,500 temperature readings came in, many from people who built the tracker themselves.

In the 2014 project Clock Your Sleep45 almost 5,000 people signed up to log sleep patterns for several weeks, either online, with a Fitbit or other device, or by using WNYC’s iPhone app built for the project.

The project had multiple on-air appearances because, Keefe said, “For a longer study, you need a reminder.”

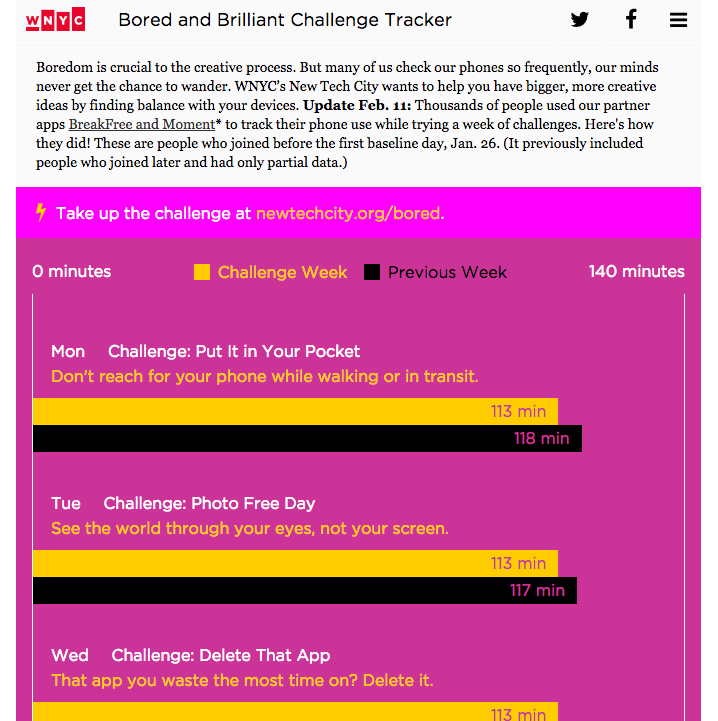

Bored and Brilliant46 enticed people with a week of challenges to put away their cell phones and “take part in a semi-scientific experiment to test your creativity.” The project nudged people to reclaim the time they spend on their phones and use it instead to let their minds wander “and see what brilliance it may lead you to.” One challenge, a photo-free day, urged people to ‘see the world through your eyes, not your screen.’”

“It was an activity you could do yourself and it made you think about

the topic,” Keefe said. More than 20,000 people took part.

“It was an activity you could do yourself and it made you think about

the topic,” Keefe said. More than 20,000 people took part.

While much of WNYC’s work focuses on engagement rather than investigations, hard news also plays a role. In Mapping the Storm Cleanup, WNYC sought to truth-check Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s assertion that snow-shoveling had been effective city-wide after a 2010 blizzard.47

WNYC invited listeners to text if their streets had been plowed. “We could map the no’s vs. the yeses. And since we had their phone numbers, we could text them back the next day, or two days later, and say, ‘Is your street plowed now?”’ Keefe said. The result: a series of maps with pins, white for unplowed and blue for plowed. Over three days of mapping, the pins turned from white to blue.

“It’s easy to get people to participate if they’re angry,” Keefe said. “It’s harder . . . if it’s benign.”

In September 2010, when New York City shifted from using voting machines to paper ballots that were marked by a voter and then scanned into a machine, WNYC launched Your New Ballot Stories, expecting ballot design to be a big issue.48

The station asked people to sign up before the vote so it could text them on voting day and, if they voted, invite them to tell what happened, or to leave a voice message that could be used on the air.

As it turned out, ballot design was not the biggest issue. Instead, voters expressed concerns about ballot privacy after being asked to hand their ballots to poll workers for scanning. “The privacy issue popped up, and that was our story right away,” Keefe said.

Accuracy is sometimes an issue, Keefe noted, and WNYC has certainly rejected some projects because they are not accurate enough. After Hurricane Sandy, he said, WNYC thought about crowdsourcing which gas stations had gas, but didn’t: first, because it couldn’t ensure the information would be accurate, and second, because people might use their last gas to get to a station, only to be disappointed. “It’s too fragile a situation to crowdsource,” he said.

That journalistic sensibility, infused with humility, lies at the heart of WNYC’s crowdsourcing.

“That’s what it’s about,” Schachter said. “It’s a genuine expression of humility that the audience, however you’re defining it for a particular endeavor, knows more than you do—and it’s to be listened to. That’s really important.”