Chat Apps and Newsgathering

Chat apps occupy a role between public broadcast and private communication, and offer a range of functionalities. Some allow small numbers of people to participate and see the same content (e.g., Facebook Messenger or Telegram). Others allow for a wider range of participants and are thus useful for news organizations at different levels of scale (e.g., WeChat and WhatsApp). Like social networking sites, chat apps present advantages and challenges for journalists covering fast-moving events. Because their functionalities vary and are constantly evolving, chat apps demand technical savvy and social nuance from journalists.

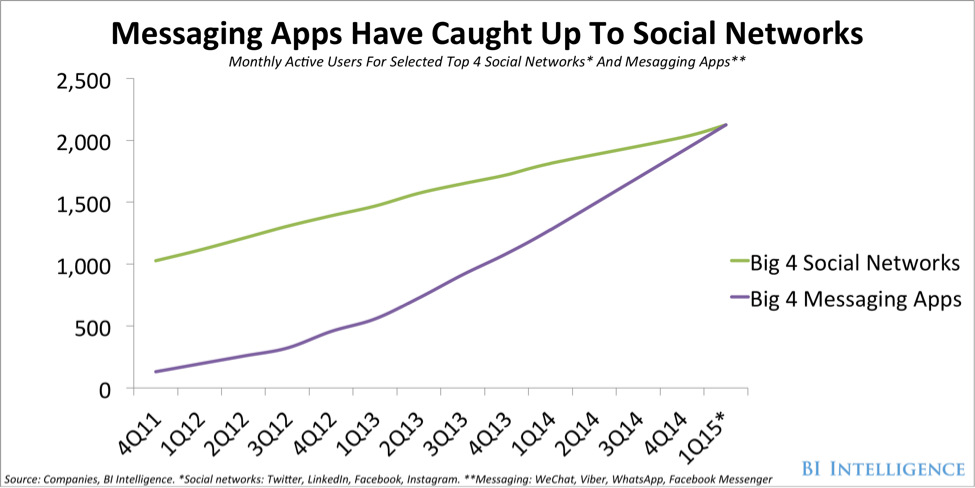

In terms of popularity, mobile chat applications have now caught up with social networking sites—and in some cases surpassed them by considerable margins. From 2011, when the earliest mobile phone chat applications were launched on the global market (Kik, KakaoTalk, and

WhatsApp), to 2015, these mobile applications reached the same number of monthly users as did the four leading social networking sites (see Chart 1). Today, the most popular chat app, WhatsApp, has more than one billion monthly active users (MAU).

Chart 1: The growth of messaging apps versus social networks

Source: Business Insider.1

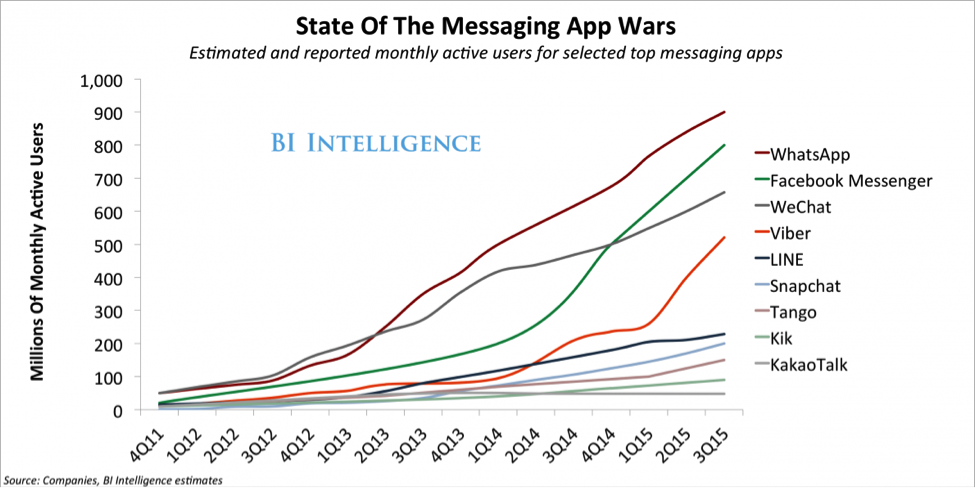

Mobile chat apps allow users to exchange information with other users in real time, using text messaging, voice messaging, and file sharing. The most popular of these apps are (in order of monthly active users): WhatsApp, WeChat, LINE, Facebook Messenger, Viber, and Snapchat (see Chart 2 for a glance at the state of messaging apps as of 2015). Some of these apps have large active user bases, such as the four hundred million users on WeChat and one billion on WhatsApp (as of 2016), while others have smaller active user bases (e.g., KakaoTalk, Kik, and Tango).

Chart 2: Top mobile messaging apps (as of Q3 2015)

Source: Business Insider.2

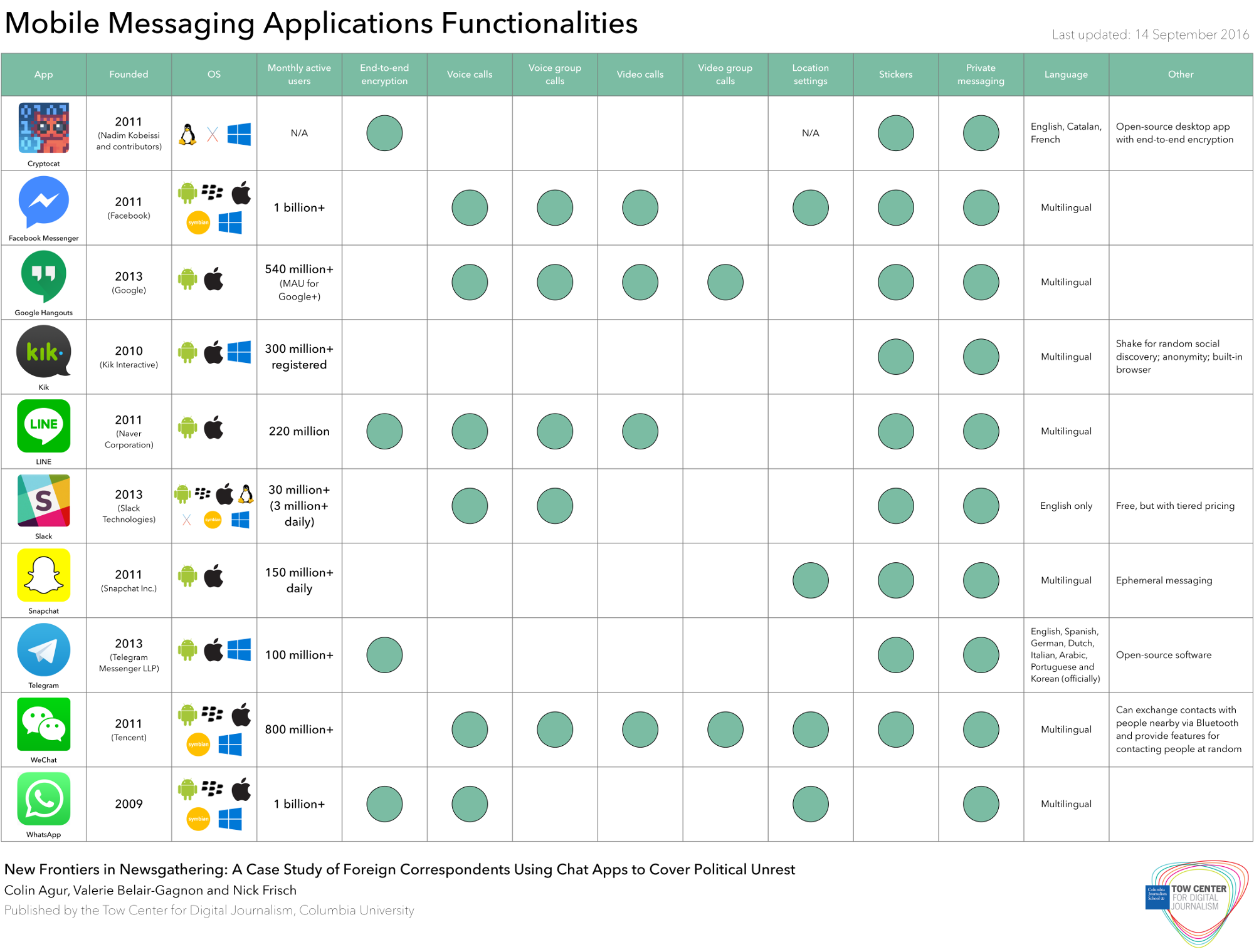

Mobile instant messaging apps are distinct from other social networking sites because of the size of their user bases, usage rates, demographics (notably young users, who are important for publishers or brands), higher user retention, and ability to connect with other users privately. The combined user base of the top four chat apps is higher than that of the top four social networking sites together. Popular in Asia, WeChat, KakaoTalk, and LINE have built strategies to keep their users engaged and monetize their services. The table highlights different functionalities these mobile applications offer.

Source: Business Insider.3

With varied functionalities, chat apps can assist news organizations with newsgathering and sourcing in domestic and international stories.4

Chat logs can provide information of potential value to companies and governments, even though the one-on-one or many-to-many conversation is supposed to be private and inaccessible. In 2013, scholars from the Citizen Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs at the University of Toronto reverse-engineered and analyzed censorship and surveillance mechanisms of the chat app LINE. These scholars uncovered that when the user set their country to China during installation of the application on a mobile device, the app enabled a censorship functionality, for example by downloading a list of censored keywords and blocking messages that contain these words.5,6

The importance of chat apps to foreign correspondents covering political unrest is rooted in the status of mobile devices as the primary digital tool in developing-world consumer markets and the growing number of “digital native” youth in developed societies. Because people involved in political unrest communicate via groups on chat apps, journalists have been able to cultivate sources and gather news by gaining access to those conversations—some private and others public.

The widespread usage of social media has introduced substantial changes to how journalists and news organizations produce news, and how they engage with audiences. For example, it is now common for images on Twitter or Facebook to make it into news production.7,8 Similarly, mobile chat applications and ensuing discussions on those apps provide opportunities for newsgathering. Chat apps can operate on top of existing social networking platforms (as does Facebook Messenger); they can also be standalone applications (like WhatsApp). Unlike many social networking sites, these apps allow for communication in real time through the transmission of text and multimedia from senders to receivers, either publicly or privately.

The arrival of open sites such as Twitter, Sino Weibo, and Instagram gave reporters new ways of finding content and sources; with chat apps, the changes are more of a mixed bag. What we are seeing is not a simple, linear progression toward greater transparency and easier newsgathering. While public sites allow reporters to find content rapidly and often with greater ease than before, closed networks limit access and can make newsgathering more complicated and labor-intensive. In this report, we emphasize the role of these new private and semi-private spaces in news production processes.

In this context of rapidly growing chat app usage, what does the rise of private social networks and chat apps mean for newsgathering? Does it mean the end of social newsgathering?

David Clinch, global news editor at Storyful, said that finding relevant chat app conversations can be a challenge. That’s why Storyful’s teams have identified people “in particular places, where WhatsApp is very useful as a newsgathering tool, who act as the nodes.”9 An Xiao Mina, a product director at software nonprofit Meedan, agreed that while contacts are easily searchable on Twitter or Facebook, the story is different on chat apps such as Telegram, Cryptocat, or WeChat. Mina spoke of the emergence of a “digital fixer,” somebody who performs ad-hoc assistance for reporters on platforms and managing data—anything from translation to local connections and knowledge. While conducting research for a project in China, Mina was introduced to a WeChat group “where 500 people were trading ideas about products and issues.” She said: “This was not discoverable by any other means. I literally needed someone to tell me the group existed, then to invite me into that group, to bring me into the circle of trust . . . Finding information on private social networks means developing sources in a more traditional manner.”10

Especially in breaking news, mobile chat apps are playing increasingly significant roles in news production and journalist-audience interactions. Around the world, users are not only logging in to messaging apps to chat among themselves, but also to connect with journalists, news organizations, and brands. This report examines how journalists at major news organizations used chat apps for newsgathering to cover the 2014 Hong Kong protests, and how chat apps have shaped their journalistic practice since.