Changing Journalistic Practice

A fundamental reason why publishers need to experiment with different opportunities for income generation is because the traditional funding model for news is broken. Technology is rapidly changing the way content is created, distributed, consumed, and monetized.107

This is all happening at such a pace that it’s easy to forget that many popular digital platforms and online behaviors are, in fact, relatively recent additions to media diets.108

In the space of a few short years, new storytelling tools like Facebook Live, Periscope, and Snapchat have quickly become part of the journalist’s toolkit, while usage of more established platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram has evolved as their functionality and audience continues to grow.109 110 111 Meanwhile, platforms like Vine, Meerkat, and Google+ have either closed or effectively been consigned to the digital graveyard.112 113

These developments have required news and media outlets to move with the audience, embracing new platforms and finding new ways to tell stories.

In this section we explore some of the ways that local newspapers are engaging with these channels, highlighting examples of practice and some of the strategic implications and challenges which many small-market newspapers are trying to make sense of.

Social media as standard (but it’s an often uneasy relationship)

For some, such as Levi Pulkkinen at Seattlepi.com, the emergence of newer and more established digital platforms can be a cause for optimism. “It’s a really exciting time for journalism,” he said, “because if you run a small newspaper, your potential audience for the stuff you’re doing has gotten gigantic in the last decade.”

The influence of these channels on our media habits is such, Pulkkinen argued, that if you’re not active on these platforms “you’re basically deciding not to play.”

There’s certainly an element of truth to that. But it’s also true to say that some local publishers are deliberately deciding not to play. This is particularly true of many smaller outlets, where resource constraints make it difficult to do everything, and be everywhere.

Moreover, for many of these titles, a reliance on physical newspaper sales means that some publishers are being careful not to cannibalize their print audience by giving away the crown jewels (for free) on social, or indeed anywhere else online. These titles still need people to buy their paper each week if they are to survive.

The Calhoun County Journal of Bruce, Mississippi (population 1,939)114 is a good example of this. With a circulation of a little over 5,000 a week, it’s the only newspaper in Calhoun County. Although active on social media, the paper purposefully eschews Facebook (although not the Facebook-owned Instagram115).

Publisher Joel McNeece, a past president of the Mississippi Press Association who sits on the National Newspaper Association Board of Directors, explained that too many small publishers “think they can stick something on Facebook and that equates to a good advertisement because thirty people liked it. It’s not generating any business for you,” he said, arguing that “your best dollar is still in print.”

For others, the challenges of this relationship go beyond just revenue. Billy Coleburn from Richmond’s Courier-Record (Virginia) was just one publisher who stressed the impact of the new digital gatekeepers on both revenues and audience time, saying, “I view my number one competitor really as Facebook and social media because you’re competing for the hearts, and minds, and the attention span of human beings. And our attention span is ridiculously small these days.”

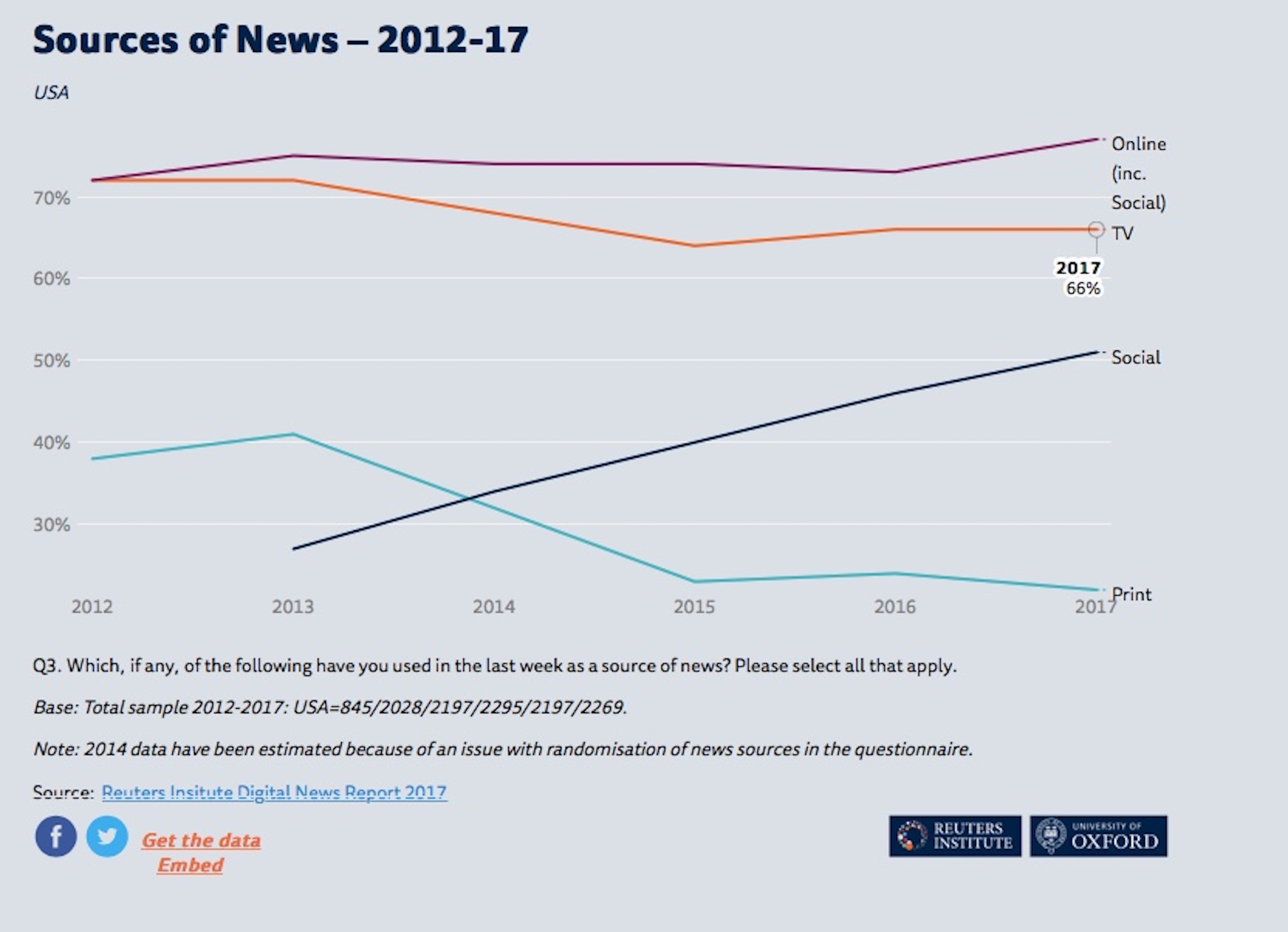

Despite these challenges, the popularity of social networks as a news source means that it takes a bold publisher to purposefully refrain from using these channels. Data from the “Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017” found that fifty-one percent of digital news consumers in the United States now get news from social media, a cohort that’s grown five percent since 2016 and doubled since 2013.116

During this same period (not long after the Waldman Report was published), print as a source for news fell precipitously. Reports from Pew have consistently told a similar story, especially among younger audiences.117118

Source: Reuters Institute/Oxford University 119

The growth of video and live video reporting

At the end of 2016 we undertook an online survey completed by 420 journalists based at small-market newspapers across the United States.120 Our research identified a cohort that is enthusiastically embracing digital storytelling, especially video and live video.121 Newsrooms are benefitting from the low barriers of entry created by smartphones and cheap (and sometimes free) editing tools, as well as new live video streaming services.

However, despite this engagement, publishers face a number of important strategic issues in this space. One key consideration is skills and training, as identified by our survey, which revealed that most journalists tend to be self-taught with new technologies, or they learn from articles on sites like Nieman Lab, Poynter, and MediaShift.

Audiences may need support and training, too, and publishers can play a role in providing compelling content which drives audiences to digital platforms, while at the same time explaining how to use/access these platforms. In doing so, news organizations can play a key role in helping to develop these types of media literacy and digital behaviors.

These platforms may be less effective for some small-market newspapers. Access issues are an important consideration, especially in rural communities where availability may be more limited. Slower-fixed and mobile broadband speeds mean that video, as well as other rich multimedia content, is not necessarily viable for non-urban publishers or audiences.

Finally, a number of interviewees also identified the unproven business and revenue models from many of these platforms as issues. As Amalie Nash, the Des Moines Register’s executive editor and vice president for news and engagement at the time of interview and now Gannett’s executive editor for the West Region, explained: “You look at something like Facebook native videos, which we all agree that’s great for brand, that’s great for getting yourself out there, and this and that, but at the end of the day, you’re making pennies on the dollar in terms of what those videos are providing as far as revenue sources.”

On other platforms, revenue may be even less. A cursory glance at the YouTube channels for many small-market newspapers, for example, shows video views often total between a few thousand and a few hundred.

“Getting five or six or seven hundred views on a single video isn’t a sellable item to an advertiser,” warned Lou Brancaccio, emeritus editor of The Columbian of Vancouver, Washington. As a result, he suggested this may not be a viable medium for smaller outlets to continue investing in so heavily. “The jury is still out on whether or not that is going to pull more viewers onto our website,” he said.

In contrast, given the need for scale and reach, video may be a format that is far more successful for larger newspapers, where views are greater and thus the opportunity for advertising or sponsorship may be more discernible. It will be interesting to see how this dynamic shapes up as the video market continues to mature.

The emerging importance—and influence—of metrics

“Metrics inspire a range of strong feelings in journalists, such as excitement, anxiety, self-doubt, triumph, competition, and demoralization,” wrote Tow Fellow Caitlin Petre in her 2015 report “Traffic Factories: Metrics at Chartbeat, Gawker Media, and The New York Times.”122

Petre observed how “metrics exert a powerful influence over journalists’ emotions and morale,” and that, for all of the positives which these tools can unlock, “traffic-based rankings can drown out other forms of evaluation.” This trend is now beginning to permeate the different tiers of local journalism.

One potential benefit of these tools, suggested Lauren Gustus, the former executive editor of the Coloradoan (Fort Collins, Colorado), is that it enables journalists and editors to quantify readership in a manner not previously possible. The conclusions can sometimes be surprising. “If you look at the metrics, you know that so much of what we do doesn’t get consumed in a way that maybe we think it does,” she said.

The impact of this can be used to realign and reframe certain types of stories, providing evidence (which is especially valuable in a climate of reduced resources) for dropping or diminishing certain beats, while also enabling newspapers to double-down on topics which really resonate with their communities.

Liz Worthington, content strategy program manager at the American Press Institute (API) who leads the Metrics For News program, argued that these types of insights can help to deepen relationships between audiences and small-market newspapers:

By focusing on a few key topic areas, you create more loyalty. The readers really respond to it . . . And the newsrooms we work with are pretty transparent with their audience about why are we doing this and why you are taking this survey to help us figure out what we should do differently. It does lead to higher page views, but also less churn, more loyalty, and hopefully deeper engagement with your audiences.

Editors at papers ranging from the Herald and News in Klamath Falls, Oregon, to The Dallas Morning News in Texas told us that they had benefitted from this approach. Others highlighted some of the cultural challenges presented by metrics, not least when they proffer conclusions that newsrooms don’t necessarily want to hear.

“I think there’s a hesitancy in the newspaper industry among reporters not to recognize what the metrics are telling us,” said Levi Pulkkinen at Seattlepi.com, namely “that we need to change the content.” Specifically, he added, “What we’re finding is that readers have very little taste for incremental coverage, and that’s the bread and butter of local newspaper[s].”

Metric-informed practices can help to achieve these ambitions, and their influence can be seen at some small-market newspapers. However, they may well encounter resistance from those wary of changes to the traditional culture and practice of journalism, and the risk that metrics can have a potentially overt influence on an outlets content mix.123

“Feeding the goat”124

Many of our interviewees come from smaller weekly publications. Journalistic practice in these environs can be very different than metros or newspapers in larger, more competitive news markets. Arguably one of the biggest differences is in the speed of publication and audience expectations around the availability of news content.

For some publishers, being weekly is an editorial asset, enabling them to take a step back and report the news differently from those caught up in the cycle of daily publishing and around-the-clock updates on social media.

But the weekly publishing schedule, while identified as a strength, can also potentially leave outlets vulnerable. Al Cross, director of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, explained how the News-Democrat & Leader—a bi-weekly paper in Russellville, Kentucky (population 7,037)—risked being left behind as audiences migrate to The Logan Journal, “an online newspaper,” its Twitter bio notes, “that is devoted to bring you the stories quicker and better.”125

For daily papers, different challenges abound. Lou Brancaccio, emeritus editor of The Columbian, a seven-day-a-week publication in Vancouver, Washington, described a fast-moving environment where publishers can’t afford to be late to a story. “The worst thing that can happen to a newspaper is that somebody reads some news from their Facebook friend, they go to The Columbian website to see if we have it, and we don’t have it,” he said.

In many cases, Brancaccio argued, the paper does have the story, but the reporter is waiting until it is complete before publishing. “That’s old-school thinking,” he said, leading him—and others—to encourage reporters to publish online when a story breaks, fleshing it out as further details emerge.

For many journalists that’s a radically different approach from the way they have previously worked. But Brancaccio believes it’s necessary for many outlets in this day and age. “The odds are somebody else has it,” he said, “and if you don’t get it up first, somebody else will.”

Social media can, to some extent, act as a halfway house between these two scenarios for some weeklies, plugging the gaps between print runs.

Les Zaitz, a former investigative reporter for The Oregonian and publisher of the Malheur Enterprise in Vale, Oregon (population 1,838), covered the standoff at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge near Burns (population 2,738), a story which garnered national attention.126 127 128

Zaitz said that due to the weekly publishing schedules of many small-market newspapers “social media is a vital information lifeline for these communities, or can be,” adding: “I was frankly astonished in Burns as I did my reporting how my personal audience in Harney County and Burns grew by the hour because people were so starved for information, and they were served only by a weekly newspaper that could only come out once a week.”

Weekly, small-market newspapers, like their daily and metro counterparts, understand that audience expectations around the availability of content is shifting. Although change may be coming more slowly, the external pressures which are reshaping the speed with which news and information is disseminated and consumed is coming their way.

The new model journalist

The journalism profession is changing rapidly.129 As a result, the majority of newsrooms are unrecognizable from how they looked at the start of the new millennium.

Many journalists are now expected to demonstrate an ever-increasing range of skills, including: being able to write, shoot video, take photographs, input their copy into a content management system, identify pull-quotes, and produce social media content for a variety of platforms.

Newsrooms at small-market newspapers are not immune from these changes. In our 2016–17 survey of journalists at small-market newspapers, seventy percent of respondents told us they spent more time on digital-related output than they did two years ago, and nearly half (forty-six percent) said the number of stories they produce has increased in the past two years.130

As newspapers have laid off personnel, remaining staff have—in many cases—needed to grow and develop their skillsets. In our interviews, editors described videographers who were being asked to learn photography (and vice versa), while many traditional beat reporters are required to write for the website, newsletters, live blogs, social channels, and the original print publication. Each of these channels requires the flexing of different writing muscles. Meanwhile, even the smallest outlets are embracing opportunities to shoot video and photographs for social, as well as broadcast on Facebook Live.

Because of this, new and emerging skillsets are being increasingly valued by newsrooms, with newsrooms restructuring to create audience teams131 and engagement specialists.132

Lauren Gustus, the former executive editor at the Coloradoan in Fort Collins, Colorado, explained how her small newsroom (thirty to forty people) had been reconfigured to include a dedicated ten-person engagement team. Part of their charge, she explained, was “talking with readers across any of the platforms that we operate on and that our readers operate on.”

Others are following suit, although based on our conversations, the core skill requirements at small-market newspapers continue to be quite traditional and mainstream.

It will be interesting to see if these differences remain, or if emerging skill areas will simply be absorbed into the tasks expected of journalists in the digital age. With many journalism schools beginning to teach or place greater emphasis on these emerging skills, the next generation may automatically bring these sensibilities to the newsroom as part of the perpetual evolution and transformation of journalistic practice that is happening across the industry.

Final thoughts on changing journalistic practice

As we have seen, journalism is an evolving profession. The pace and extent of this change varies from outlet to outlet, and many journalists may find this evolution rather daunting.

Nonetheless, as Margaret Sullivan famously said, “These days, being a journalist shares at least one quality with being a shark. If you’re not moving forward, it’s over.”133

Small-market newsrooms across the country are moving forward by embracing social media and video, engaging with analytics and metrics tools, and reevaluating their publishing practices. These trends, and arguably the pace of change, show no signs of slowing.