Hate Crimes Against Muslims

Even though we spend an increasingly larger fraction of our time navigating and participating in conversations and activities based in cyberspace, the virtual realm is often considered less real than the physical world, with different rules. In her book Hate Crimes in Cyberspace (2016), law professor Danielle Keats Citron3 explains how this cultural premise of a lesser reality translates into the notion that “more aggression should be tolerated in cyberspace than in real space” and that “virtual spaces are cordoned off from physical ones.” This premise, Citron argues, is untrue, and the work of cyber law scholars such as Julie Cohen has illustrated Citron’s thesis that “logging off,” so to speak, is largely a myth and that “harassing posts are situated wherever there are individuals who view them and thus they have a profound influence over the lives of victims.” The myth of cyberspace as a lesser reality has permitted it to become another realm where minorities—such as women, Muslims, and homosexuals—are targeted, often with few or no consequences for the harassers.

Google Searches as Indicators and Predictors of Hate Crimes

The connection between online behavior and racial animus has been studied by social scientists on the basis of data from the 2012 electoral race. One such study of racial animus in the 2012 US presidential election found that the percentage of Google searches including hate speech or racially charged language serves as a meaningful proxy for levels of racial animus in a given area, and predicted Obama’s vote share with greater accuracy than survey data.4 The study finds that juxtaposing what people search for online and their physical location is a reliable predictor of how they vote in real life elections. One explanation for the study’s findings is that the private nature of Google searches makes Google data less likely to be marred by social desirability bias. This means that people frequently express socially taboo thoughts in Google searches (as the large number of searches for pornography and sensitive health information suggests5), typing in the search bar thoughts and questions they would not share with even closes friends and family. Unlike social media activity (which can also engage in the presentation of such views via fake pseudonymous profiles), Google searches present what the majority of people believe to be “unseen” behavior. Recent work by Seth Stephens-Davidowitz also suggests that the incidence of Islamophobic hate speech in American Google searches is correlated with the frequency of hate crimes. This bears particular relevance to the current electoral campaign, where Islam and Muslims have been front and center and where the statements of the GOP candidate have declared Muslims worthy of a blanket immigration ban.

A look at the frequency with which Americans are searching for Islamophobic terms, where most of these searches take place, and when spikes in these searches occur, then, can approximate how widespread Islamophobia is among Americans. Contrasting this data against the prevalence of Google searches related to Islamophobia (a proxy for concern about anti-Muslim bias) allows us to see how the frequency of expressions of Islamophobia compares with that of anti-Islamophobic views among Americans.

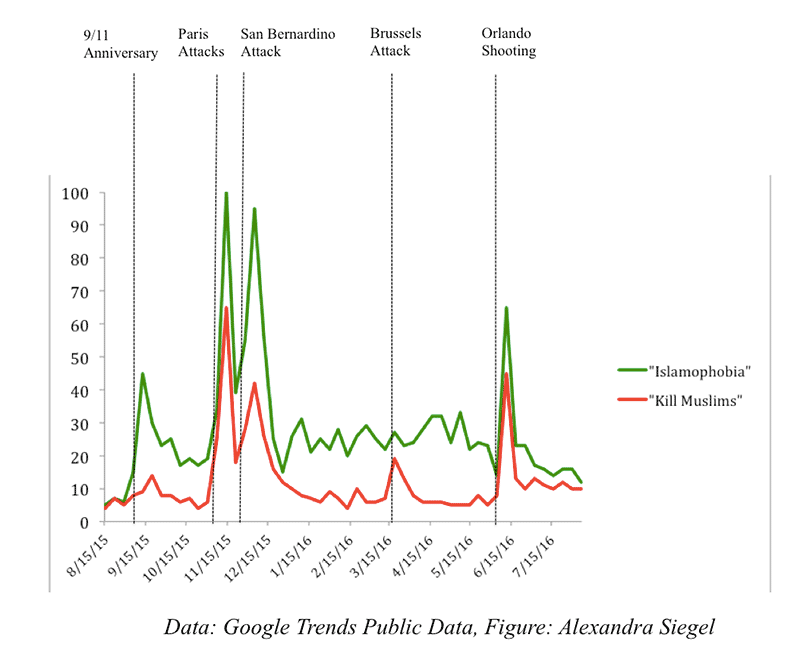

As the normalized plot of Google Trends data below indicates, the term “Islamophobia” was more commonly searched than “Kill Muslims” every week for the past year. According to Google Keyword Planner, which provides the average monthly search volume of a given keyword, over the past twelve months, the monthly average number of searches for “Kill Muslims” and variations ("Kill all Muslims," "Kill the Muslims") was 1,890, with a peak of 6,590 searches in November, 2015, and a low of 690 searches in August, 2015. By contrast, the monthly average number of searches for “Islamophobia” was 22,200 with a peak in November of 2015, of 49,500 and a low in August of 2015, of 5,400. There were peaks in both anti-Muslim and Islamophobia Google searches following the Paris attacks on November 13, 2015, the San Bernardino attack on December 2, 2015, and the Orlando shooting on June 12, 2016. There is also a large spike in the search term “Islamophobia” on the anniversary of 9/11, and a large spike in “Kill Muslims” following the Brussels attack.

Google Trends data also show the “top related topics” or most-searched topics by Google users who searched for the keywords in question. Among the top related topics for those searching “Kill Muslims” were the terms “ISIS,” “Christianity,” “Donald Trump,” “Terrorism,” “Jewish People,” “Bible,” “Jesus,” and “Barack Obama.” The top related topics for those searching “Islamophobia” included “Racism,” “Xenophobia,” “Donald Trump,” “September 11,” “Refugee,” and “Discrimination.” The prevalence of discussion of Donald Trump among users who searched both Islamophobic and anti-Islamophobic keywords strengthens the sense that Trump’s candidacy has served to increase the saliency of anti-Muslim bias as an election issue.

Weekly Relative Frequency of Google Searches for “Kill Muslims” or “Islamophobia” (August 2015–August 2016)

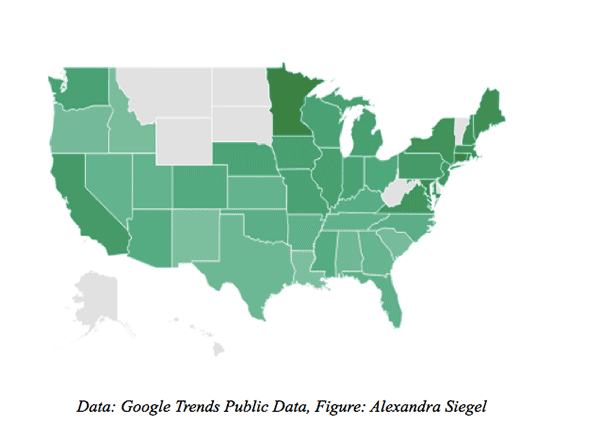

The regional breakdown of Google Trends data suggests that searches for both “Islamophobia” and “Kill Muslims” are prevalent across the country.

Note: Numbers on the Y-axis represent search interest relative to the highest point on the plot for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. Likewise a score of 0 means the term was less than 1 percent as popular as the peak.

Variation in Relative Volume of “Islamophobia” Searches by State (August 2015–August 2016)

Note: Darker color indicates a higher relative search volume. Gray color indicates a very low volume of the search term.

Variation in Relative Volume of “Kill Muslims” Searches by State (August 2015–August 2016)

Note: Darker color indicates a higher relative search volume. Gray color indicates very low volume of the search term.

The only state in which the relative volume of searches for “Kill Muslims” outnumbered the relative volume of searches for “Islamophobia” was Louisiana. As the table below indicates, the term “Kill Muslims” had one of the highest relative frequencies in Louisiana, while the term “Islamophobia” had one of the lowest.

Relative Prevalence of “Kill Muslims” vs. “Islamophobia” Google Searches by State (Red and Blue States) (August 2015–August 2016)

| “Kill Muslims” | “Islamophobia” | |

| Minnesota (D) |

Note: This table ranks states by the relative prevalence of each search term. States are not included on this list if the relative volume of the search term is too low. Red states are states where Mitt Romney won in 2012 and blue states are where Obama won in 2012.

As can be seen, the data on Google searches present some disturbing results. It is not surprising, of course, to note that the volume of searches surges around the anniversary of the 9/11 attacks and the Orlando and San Bernardino mass shootings. However, what is notable is that the number of people who search terms like “Kill Muslims” is not significantly lower, and in one state (Louisiana) is actually greater than the number of searches for “Islamophobia.” The numbers for “Kill Muslims” also need to be considered in light of the wider patterns of hate searches outlined by Stephens-Davidowitz. In his essay “The Rise of the Hate Search,” he writes: “There are about 1,600 searches for “I hate my boss” every month in the United States. In a survey of American workers, half of the respondents said that they had left a job because they hated their boss; there are about 150 million workers in America,” leading us to the conclusion that if everyone was searching for what they were experiencing the numbers would be much higher. In this case, in November, 2015, there were about 3,600 searches in the United States for “I hate Muslims” and about 2,400 for “kill Muslims.” These Islamophobic searches likely represent a similarly tiny fraction of those who had the same thoughts but didn’t drop them into Google.

If Islamophobia search statistics are considered a proxy for sympathy toward Muslims, or concern for their rights, then “Kill Muslims” suggests exactly what it stands for: a desire for the elimination, literally the killing, of Muslims. The second statistic should be truly alarming. While hate exists in every country, those who respect the constitutional rights afforded to religious minorities should greatly outnumber those who consider killing them. Second, the fact that Islamophobia is a complex term suggests that those searching for it may not necessarily know its meaning or simply be looking for a definition while those searching for “Kill Muslims” are unlikely to be doing so. This suggests that while the numbers of people searching for Islamophobia may not actually be sympathetic to toward Muslim Americans, there is very little doubt that those searching the term “Kill Muslims” bear animus toward them. Finally, the fact that primarily Republican states rank in the top three for the “Kill Muslims” search also suggests that the rhetoric used by the Republican Party during its primary season, and then later by nominee Donald Trump, has actual implications in their adherents’ sentiments about Muslims, mirrored here in their searches for “Kill Muslims.” Since civil rights laws and protections are available to all Americans, it is troubling to see respect for the rights of American Muslims translated into a partisan issue where having a particular political affiliation can mean a refusal to support religious freedom for American Muslims.

Social Media and Islamophobia

Beyond what people Google anonymously, Twitter and Facebook data also provide key insights into the prevalence of anti-Muslim hate speech online. Like Google Trends data, studies suggest that the relative popularity of hate speech on social media serves as an early warning sign of instability and potential violence. In fact, tools have recently been developed and used by government and NGOs to measure the online prevalence of hate speech in order to predict outbreaks of violence. Such tools include Hatebase and Una Hakika—crowd-sourced databases of multilingual hate speech.6

In order to measure the relative volume of anti-Muslim hate speech on social media in the 2016 election period, this paper first relies on a Twitter dataset collected through NYU’s Social Media and Political Participation Lab. This dataset contains all mentions of Trump, Hillary, or Election 2016 from April, 2015, to July, 2016. Filtering this dataset in order to measure the prevalence of anti-Muslim and anti-Islamophobia tweets, there are 5,773,466 tweets that contain the terms “Muslim or Islam.” 83,954 of them contain anti-Muslim terms and do not contain anti-Islamophobia terms. 118,417 of the tweets referencing “Muslim” or “Islam” contain anti-Islamophobia terms and do not contain anti-Muslim terms. Tweets that contained both types of references were not included, as the sentiment of these tweets is unclear. Then, the following common hashtags were used to determine whether tweets were “anti-Muslim” or “anti-Islamophobia.”7

| Anti-Muslim Hashtags

| Anti-Islamophobia Hashtags |

| #islamistheproblem | #islamophobia

|

In addition to Twitter data, a look at a dataset of Election 2016 Facebook data allows for a cross-platform comparison of pro- versus anti-Islamophobic sentiments. In particular, scraping recent posts on Donald Trump’s and Hillary Clinton’s Facebook pages provides further insight into the salience of anti-Muslim sentiment during the lead up to the 2016 election. While API limits only allowed us to scrape data from March of 2016 forward, we nonetheless observe interesting trends over the past several months.

Out of 4,492,925 comments on Clinton’s Facebook page and 7,670,262 comments on Trump’s Facebook page, 121,618 comments mentioned the terms “Islam” or “Muslim,” posted by 68,464 unique users. Of these posts, 9,110 contained anti-Muslim terms posted by 4,546 unique users and 2,094 contained anti-Islamophobia terms posted by 721 unique users. Again, we did not include posts that contained both anti-Muslim and anti-Islamophobia terms, as the sentiment of these posts is unclear.

The trends drawn from the data on Google searches recur in the data from Facebook and Twitter. On Twitter, as the graphs in the appendix demonstrate, the largest spikes in anti-Muslim election-related tweets occurred following the Brussels attacks and the Orlando attack. We also observe smaller spikes following the Paris attack and the San Bernardino attack. The largest spike in anti-Islamophobia tweets also occurred around the San Bernardino attack in December 2015. On Facebook, the figures in the appendix show that the biggest spike in anti-Muslim comments occurred following the Orlando attack, while the biggest spike in anti-Islamophobia comments occurred during the DNC during the Khizr Khan speech. Politicians’ Facebook pages were the one platform on which anti-Muslim rhetoric was far more prevalent than anti-Islamophobia rhetoric.

It is notable that the attacks in Orlando and San Bernardino prompted candidate statements. On the day following the Orlando shooting, Trump delivered a speech in which he asserted that “the killer, whose name I will not use or ever say, was born an Afghan of Afghan parents, who immigrated to the United States.” He also said: “Large numbers of Somali refugees in Minnesota have tried to join ISIS.” Both of these claims are untrue: Omar Mateen was born in the United States and only nine Somali Americans have ever been charged with a terror-related offense.

In the same speech, Trump interpreted President Obama and Clinton’s refusal to use the term “radical Islamic terrorist” (owing to its implication of terror as a particularly Islamic phenomenon) as actual support for extremism. Trump also falsely asserted that people in San Bernardino had known about the attacker’s intentions, but failed to report because they were concerned with racial profiling. In sum, Trump conflated Muslims with terrorists and suggested that the terrorist was not American because his parents were Afghan.

In her speech, also delivered on June 13, Clinton expressed both outrage at the horror and sympathy for the victims. Instead of using “Muslim” and “Islam” to describe the shooter, she mentioned ISIS. One of the few times the word “Muslim” did appear in her speech was when she mentioned that “they (ISIS) are slaughtering Muslims who refuse to accept their medieval ways” in an attempt to underscore that Muslims are the most common target of terror attacks.

The content of the posts on the Facebook pages of both candidates immediately following the attack reveals the consequences of these rhetorical differences, one eager to hold all Muslims and particularly American Muslims as responsible for and sympathetic to terrorism (meriting a ban) and the other who has refused to use Muslims as bait in her campaign rhetoric. Between June 12 and 14, 297 anti-Muslim comments were posted on Clinton’s official page and 703 were posted on Trump’s page. The total number (until July 2016) of anti-Muslim comments on Clinton’s page was 3,090, while the total number on Trump’s page was almost double that at 6,020.8

Instead of there being widespread support for constitutionally guaranteed religious freedom, Islamophobic tweets (84K) came up to almost two-thirds of the tweets that were against Islamophobia (118K). This becomes an even greater basis of concern when it is noted that most of the anti-Muslim hashtags for which data were pulled involve violent acts against Muslims or their places of worship. It is also notable that a fewer number of unique users generate a high number of anti-Islamophobia tweets relative to the number of unique users that generate Islamophobic content. This suggests the possibility that the anti-Islamophobic tweets may be produced by a small number of activists who oppose hate speech on the internet against the larger number searching, tweeting, and sharing Islamophobic material.

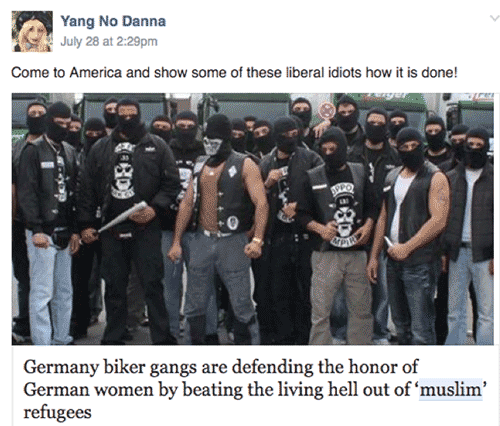

Looking at some of the most egregious tweets and Facebook posts underscores the potential dangers posed by the numeric proximity between those that speak out against hate groups and in favor of protecting minority rights versus those who actively believe in the extermination of Muslims and are not afraid to state their views in public. The Facebook post below, for instance, seeks to inspire white men to beat up Muslims in order to defend the honor of white women.

The anti-Muslim post below uses an anti-hate position to preach hatred against Muslims by saying that all Muslims constitute a hate group that should be banned.

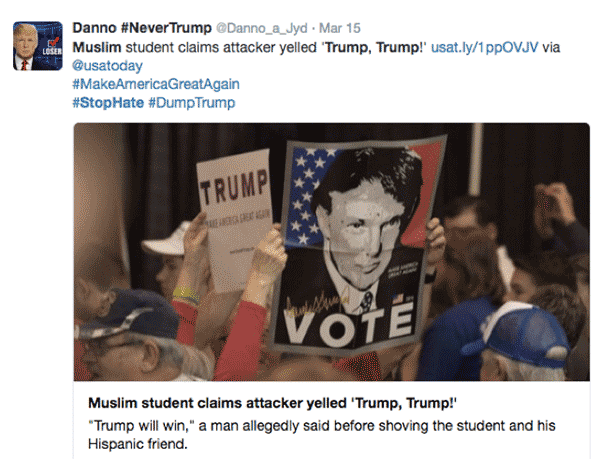

The following is an example from Twitter users who are against Islamophobia and hatred. Unlike the posts above, which seek to provoke violence against Muslims or their places of worship, it shares an article about a hate crime against a Muslim student committed by an alleged Trump supporter.

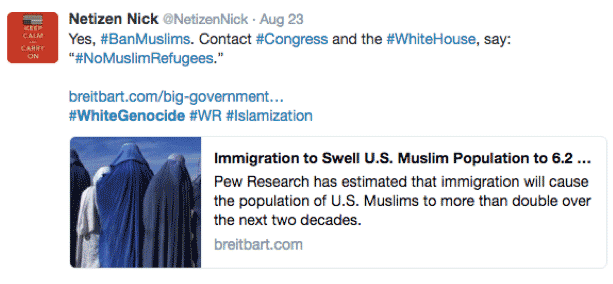

Finally, the tweet below urges others to call their electoral representatives and demand a Muslim ban. The fact that it originates from Breitbart.com, a news site whose top executive is now the CEO of Donald Trump’s electoral campaign, underscores the candidate’s particular avowal of Islamophobia as a campaign strategy.

Hate Crimes Against Muslims Since June 2016

On August 13, 2016, Imam Maulana Akonjee and his assistant Thara Uddin were walking home from the Al-Furqan Jame mosque in the predominantly Muslim neighborhood of Ozone Park in Queens New York. As they were walking home, a man approached them from behind and shot them in the back of their heads. The men were transported to Jamaica Medical Center in Queens, where they were declared dead. They had been wearing visibly religious garb when they were shot.

The assailant was later identified as 35-year-old Oscar Morel, a man who lived in Brooklyn and had no prior connection to the Ozone Park Mosque. Ten minutes after he shot the Imam and his assistant, he drove his black SUV into an Iraqi man named Salim al-Shimiri, who was walking his bicycle through a crosswalk. Al-Shimiri was struck and fell to the ground, badly bruised but alive. Bystanders called the police and reported a hit and run; footage from a nearby surveillance camera saw the SUV hit the man and speed off. The murders and the hit-and-run together fueled fear among the mostly immigrant Ozone Park community.

The Council of American Islamic Relations, a Muslim civil rights group, said the incident was a hate crime a few days after the shooting: “You can’t just go up to a person, shoot them in the head, and not be motivated by hatred.” But on Friday, August 19, 2016, the District Attorney of Queens released a statement that Oscar Morel was being charged only with first-degree murder; second-degree murder would be the minimum required if he were being charged with a hate crime. As The New York Times’ report of the DA’s charging decision suggests, this was a political move, one that stayed true to the “technical” aspects of the law. While authorities expressed “deepest sympathies” for the victims, the criminal justice system did not pursue an adequate investigation into the motives for the killings.

Dismissing the possibility that crimes against, even murders of, American Muslims are motivated by hatred or Islamophobia is not exclusive to the Queens District Attorney’s Office. This penchant for ignoring the threats (and actual violence) to which Muslims are subject is even more pronounced online. When Tamim Uddin, Uddin’s nephew, posted about his uncle’s death on Facebook, a man posted, “You were warned not to mess with the West and now you must suffer thy consequences. Tick Tock…TRUMP2016. Death to all who challenge Western Civilization.”

The murder of Akonjee and Uddin is one among many hate crimes directed at Muslims during this election season. A recent report, “Protecting Pluralism: Ending Islamophobia,” prepared by the BRIDGE initiative at Georgetown University, looked at Islamophobia in two distinct time periods to get an idea of how Islamophobic rhetoric was influencing hate crimes against Muslims. The report states that during the election season (defined for their purposes as the period from March, 2015, to March, 2016) there were 160 incidents of anti-Muslim violence, including twelve murders (not including the Queens murders).

The first surge in anti-Muslim rhetoric took place in September, 2015, and was seen to correspond with an international event: the Syrian refugee crisis. November and December of 2015 saw the Paris and San Bernardino terror attacks,9 following which Trump made a call to shut down mosques and ban Muslim immigrants. Anti-Muslim attacks tripled during the following month. It is also notable that over half of the seventeen attacks during that month (also unlike previous months) were directed at mosques and Islamic schools. Attacks during this month constituted a third of all the attacks in 2015.

Federal Hate Crime Legislation and its Failure to Protect American Muslims

The Akonjee and Uddin murder in Queens was not the only incident for which authorities refused to charge an Islamophobic assailant with a hate crime. In February, 2015, a grand jury in North Carolina delivered an indictment against 46-year-old Craig Hicks for killing his Muslim neighbors, Deah Barakat, 23; Yusor Abu-Salha, 21; and Razan Abu-Salha, 19. There was no mention in the indictment of the triple murder being a hate crime. While there had been a parking dispute between the two parties, Hicks had posted many anti-religion posts on his social media accounts, and neighbors said he had become more hostile when Yusor Abu-Salha, who wore a headscarf, had moved into the apartment.

Even when crimes as egregious as murder seem to be motivated by Islamophobia, that motivation is rarely investigated or taken seriously. Unsurprisingly, this makes Muslims less likely to report hate crimes. A Pew Survey looking at FBI Hate Crime Reporting Database found that between 2011 and 2013, 180 hate crimes had been reported. However, when they posed the question anonymously to Muslims, asking them if they had been threatened or attacked, they found 6 percent of Muslims said that they had experienced such behavior. Based on the American Muslim population in 2010 (2.6 million), this means that 156,000 Muslims experienced threats and attacks. The Justice Department finds that two out of three American Muslims do not report the hate crimes they have experienced because they do not believe anything will be done about it.

The higher number is substantiated by the Google search and social media data presented at the outset of this section. The two are particularly troubling when considered in conjunction, since the increasing rate of hate incidents against Muslims suggests a possible connection between virtual hatred and real crime.

Most states have local civil rights statutes against hate crimes, but their provisions are neither uniform nor easily accessible to American Muslims. The Federal Hate Crime Statute 18 USC Section 249(A) and (B) criminalizes any act that “willfully causes bodily injury to any person or, through the use of fire, a firearm, a dangerous weapon, or an explosive or incendiary device, attempts to cause bodily injury to any person, because of the actual or perceived religion, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability of any person” but does not have any specific provision for online harassment. Despite the existence of these laws, as the Akonjee and Hicks cases illustrate, there is reticence in their utilization as a means to punish assailants acting on the basis of Islamophobia.

Elonis v. United States (2015) illustrates how challenging it is to get beyond First Amendment protections for speech when a person is threatening violence in online posts. It sets a dangerous precedent for the protection of hate speech online. In this case, Anthony Elonis was convicted under 18 USC 875(c), a Federal statute that criminalizes anyone who “transmits in interstate or foreign commerce any communication containing any threat to kidnap any person or any threat to injure the person of another.” Elonis had been posting threats to injure his co-workers, his wife, a kindergarten class, the police, and an FBI agent on Facebook. He was charged under the statute, and after the trial the judge instructed the jury that they were to make a finding of guilty if his statements constituted an “objective intent to threaten.” The jury came back with a guilty verdict using the “objective standard” of whether a reasonable person would have considered Elonis’s threats credible.

When Elonis appealed his conviction in June 2015, the US Supreme Court ruled that the wrong standard had been applied. In the Court’s view, the prosecution was required to prove not simply that an “objective” person would consider the posts as representing a threat but rather that Elonis subjectively intended the posts to be threatening. This constitutes a greater burden of proof than the objective standard. The Court’s rationale in insisting that the subjective standard be used was based on the premise that an objective standard did not adequately differentiate between innocent and accidental conduct versus purposeful and wrongful acts. It did not, however, specify what the correct jury instruction should have been in this case. The consequence of the Elonis decision is a discarding of the “objective” standard. It also established a gray area on the issue of what sort of jury instruction should accompany a finding of subjective intent to post a threat, and what factors would constitute adequate proof of “purposefulness” on the part of people who post them.